How much is too much of a good thing? Ask any hot rodder or truck owner with something to tow and he'll tell you there's no substitute for cubic inches, and you can't have too much torque! The crew of motorheads at Smeding Performance (Rancho Cordova, California) keeps coming up with powerful stroker engine combinations for both Bow Tie and Blue Oval fans. Their latest is a bluer-blooded 392-cubic-inch powerplant perfect for your fat-fendered or slab-sided Ford truck.

Based on a new Ford Racing block that is basically a 351 Windsor design, the Smeding 392 combines a long arm (.350-inch) with a proven assemblage of choice aftermarket components for big-block torque and horsepower from an engine that looks similar to a stock FoMoCo 302. There are certainly other ways to get 392 cubic inches and the resultant low-end torque, but resurrecting an original Chrysler 392 Hemi engine from the '50s can be frustrating. First you have to chase down all the components; then there's the time it takes to get the rust-removal and machine work done; and in the end you've got a large hunk of cast-iron in your engine compartment (and a transmission to go with it), not to mention an equally large dent in your wallet. Instead, consider that the Smeding 392 may have an easier fitment in older trucks; every single part is brand new; one could be on its way to you in a matter of days; it's already run in and tested on the dyno; and you've got a warranty!

Why is torque so important, especially for trucks? It's all about how work is measured. Even since old James Watt in the 1600s compared the output of his steam engine to that of a draft horse, torque and horsepower have been perhaps the most-remembered terms from high school physics. To make a crude comparison, the difference between them is like an arm-wrestling competition. The power you put out to turn down your opponent's arm is the torque. How fast you do it is horsepower. In the case of internal combustion engines, torque is the twisting force applied to the crankshaft on a running engine. It's what you feel in the seat of your pants when you step on the right pedal. Horsepower is also important, but more so where time is critical, as on a dragstrip run. Peak horsepower generally occurs at a higher rpm than peak torque, and the lower the rpm for that peak torque, the more responsive your truck is going to feel. Let's face it, most of us classic truck fans aren't abusing our vehicles at the drags every weekend-we're more likely to be cruising or towing a boat or a vintage RV trailer. OK, maybe we like to beat the occasional Bimmer across the intersection, but that's the forte of torque and Smeding's 392 stroker Ford motors. A torquer like this one is especially useful in today's combo of large rear tires and overdrive automatics, which can kill highway passing power.

On the tech side, the engine build starts with brand-new Sportsman II blocks from Ford Racing. Designed for circle-track racing, these blocks are like a 351 Windsor, except that they have thicker cylinder walls and beefier webs for the main bearings. They're also roller-cam ready, but are delivered "semi-finished," so you have to bore and hone the cylinders to size and do a few other machine shop operations, then thoroughly clean the block. For most big stroker assemblies, the bottom of the cylinder bores must be ground for rod/rod bolt clearance since the crank is swinging a larger arc than a stock one. Smeding has several small-block Ford stroker packages, from the popular 347 for the 302 block to the 392 and 427 engines that start with a 351-sized block. The 392s arrive at their displacement by being bored and finished to .030-inch oversize, while the new nodular-iron stroker crank has .350-inch additional stroke than a stock 351's 3.50 inches.

The rotating/reciprocating assembly is the intestinal fortitude of a performance engine like this, and the stroker crankshaft is thoroughly balanced and checked for straightness. The forged rods are fitted with low-friction floating pins, which connect them to special Keith Black/Silvolite hypereutectic pistons. The pistons feature an anti-ring-float groove between the first and second compression ring grooves and a large dish in the domes to achieve a final compression ratio of 9.8:1, which is fine for truck use with available pump gas (not the low-octane stuff, though). The beefy rods are heavier than what might be used for a race motor, so sometimes a little "Mallory metal" has to be added to the crank to sweeten its relationship with the rod/piston combo.

The engine room at Smeding Performance is where all the balanced, machined, and cleaned parts come together under experienced hands to be developed into a performance engine that can deliver with a warranty. What we used to call "blueprinting" means checking every critical measurement and changing or machining parts to achieve the desired clearances. We're going to watch parts of this process as this 392 Ford bad boy comes together. Of course, we don't have room here to show every step we photographed, but suffice it to say things are done thoroughly.

The roller-cam-ready Ford Racing block is treated to a hydraulic roller cam whose specs vary based on the customer's input on his specific application. This one had 222 degrees duration on the intake and 232 on the exhaust at .050-inch lift, and .505/.532 lift on the intake/exhaust. It helped this particular 392 pull 457 ponies yet achieve a broad torque curve-over 400 lb-ft from 2,500 rpm all the way to 5,600 rpm! The cam is rotated by a double-roller timing chain and gears. What's on top of the potent combo is a pair of aluminum Edelbrock Performer RPM cylinder heads with stainless steel valves. They're great out of the box, but at Smeding Performance, they disassemble new heads before installation and check all the guide and valve dimensions and clearances for that extra edge.

The heads are installed with Fel-Pro blue gaskets and ARP high-strength head bolts, after which the remainder of the valvetrain can be installed. The Edelbrock heads already come with pushrod guide plates for performance use. Hardened-steel pushrods are lubed and slid into place, followed by aluminum roller rocker arms (anodized blue, of course) with positive-lock adjusters. The rockers are the stock 1.6:1 ratio, though they offer reduced friction and are a "true" 1.6:1, whereas stock rockers (of any OEM manufacturer) have considerable variation, by high-performance standards, at least.

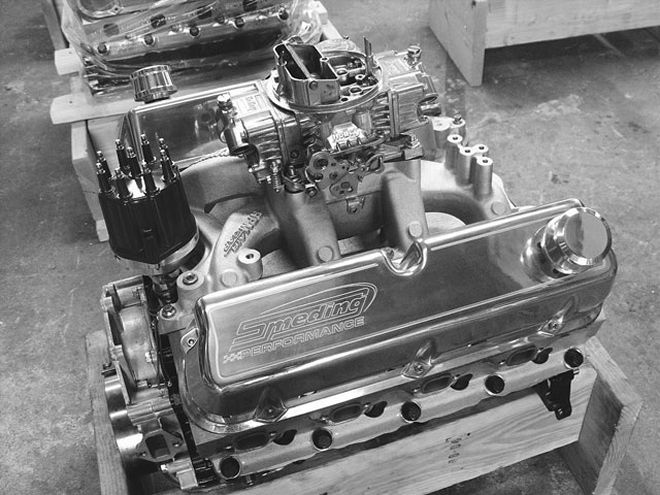

Final exterior hard parts go on next, including polished-aluminum valve covers with the Smeding Performance logo and an Edelbrock aluminum intake, in our case the Performer RPM Air-Gap model. In this performance design, extra engine heat is kept out of the intake tract by the air separation between the floor and the runners. Depending upon the specifics of the customer's application, several different oil pans may be used. On our example, we used a chromed OEM-style oil pan, but some applications for serious track use will receive a Canton fabricated oil pan with extra capacity and trapdoors around the oil pickup area.

A new aftermarket crankshaft dampener and flywheel, stick or automatic, are torqued in place, and the engine is ready for a trip to the dyno room. The engine is on a stand that rolls right up to the dyno and is connected to the dynamometer's input shaft. While in the dyno room, technician Ed Jerrell installs an appropriately sized Holley four-barrel carb and a Pertronix distributor with 8mm silicone-jacketed plug wires. After making all the fuel, coolant, and electrical connections, Ed cranks the engine to check the rough timing and lights the beast off.

What do we call this thing, Goliath or David? Sitting there purring after breaking in with all the carb and timing adjustments made, it still looks like a small-block Ford, but it sounds like a V-10! Everybody lies about their engine's horsepower, but the Smeding customer not only gets the dyno sheet on his particular engine to back up a boast, but also gets the satisfaction that the engine is already partially broken in and should run right out of the box, er, make that pallet, since Smeding doesn't ship their stroker motors in a crate. Ever fired a new engine and only then discovered fluid leaks and other concerns? With this 392, there should be no drips, runs, or errors.

Put a 392 emblem on the side of your F-1 and watch if some guy in a Duster doesn't come alongside and ask, "Has that thing got a Hemi in it?" If you don't mind the environmental effect of clouds of tire smoke, you could demonstrate to him just how good the Ford 392 does with wedge heads and a small package!