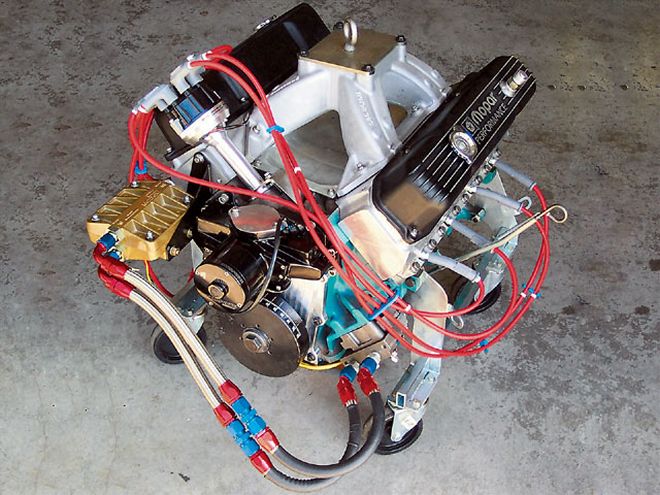

Our little 432 stroker motor looks really racy with the Victor 383 manifold, electric water pump, and external oil filter plumbing. But with a conservative 10.0:1 compression, driving down to the local cruise night is a viable option.

Our little 432 stroker motor looks really racy with the Victor 383 manifold, electric water pump, and external oil filter plumbing. But with a conservative 10.0:1 compression, driving down to the local cruise night is a viable option.

The Situation

We recently learned that Diamond Racing has introduced a new line of forged pistons for 383 stroker engines. these flat-top pistons are designed to produce around a 10.0:1 compression ratio when used with a 3.75-inch stroke crankshaft and 84cc heads (read Edelbrock). Well, that news sounded great to us since we had a clean '67 vintage 383 block sitting under the shop bench, along with a crankshaft that had been rescued from a rusted-out 413. So we whipped out the VISA card, grabbed the phone, and started in on project 432.

The Short-block Combination

One of the first questions that people will have about this combination is why bother stroking a 383 block when stroked 400 blocks are all the rage? After all, putting the 3.750 stroke crank from an RB motor into the 400 block yields 451 ci rather than 432, and the bigger bore of the 400 allows the motor to breathe a little easier. those are all good points, but we had a nice clean 383 block sitting in our garage all ready to be used in a project. And since Ma Mopar cranked out about 3 million of these little 383 blocks back in the day, the odds are pretty good that plenty of you readers have them sitting in your garages also.

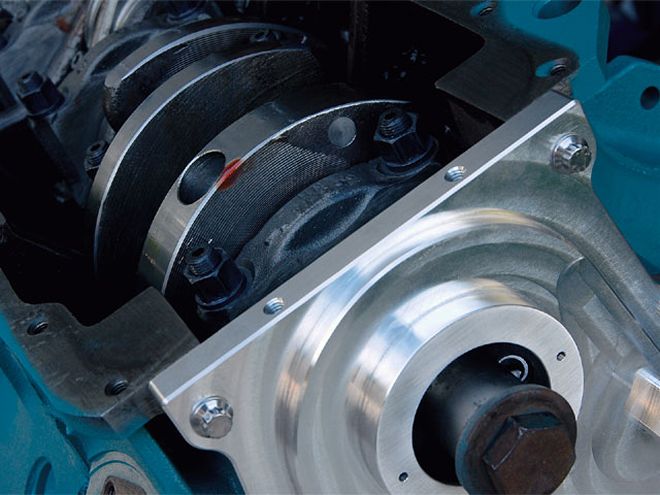

Putting a 3.75-inch stroke crankshaft from an RB motor into a B-block takes a little bit of machine work, but it isn't anything that a fairly well-equipped shop can't handle. The mains need to be turned down to the B-block size of 2.625 inches from the RB size of 2.750 inches, and the counterweights need to be trimmed down or heavily chamfered so they'll clear the main webs. Since we knew we would be using a lightweight rotating assembly, we went ahead and turned down the counterweights on a lathe to an overall diameter of 7.20 inches. This was small enough so it had plenty of clearance in the block, and it reduced the weight enough so the assembly was easy to balance.

The Diamond pistons we used are designed to work with 440-length rods, but since they require a 0.990-inch piston pin, a stock 440 connecting rod won't work unless the pin bores are machined. Reworking a set of stock rods can get expensive by the time all the necessary work is complete, so we decided to check out what the aftermarket had available. We found a company by the name of 440Source that is selling forged I-beam big-block rods with 0.990-inch wrist pins, and big 71/416 ARP rod bolts for only $395 a set. That price seemed too good to be true, but we ordered up a set and took them to our machinist. As far as he could tell, the quality on these rods was excellent for the price. The rod bolts are high-quality ARP units, the bore sizes and concentrics looked good, and the fit and finish was better than expected. We're not trying to convince you these rods from 440Source are better than, say, a set from Carrillo, but for this particular engine combination it was a better deal to buy these rods for $395 than it was to rebuild a set of 30-year-old LYs.

We had to add a small piece of Mallory in one counterweight to get the crank balanced properly. Final bobweight was right at 2,200 grams, which is great for a big-block with steel rods. The rods we used weighed 775 grams, but there is a lighter version available from 440Source that only weighs 730 grams.

We had to add a small piece of Mallory in one counterweight to get the crank balanced properly. Final bobweight was right at 2,200 grams, which is great for a big-block with steel rods. The rods we used weighed 775 grams, but there is a lighter version available from 440Source that only weighs 730 grams.

We had gotten the wrist pins and the rings from Diamond when we purchased the pistons, but we still needed bearings. For those, we ordered a set of coated pieces from Callies. We have used the Callies coated bearings in our recent engine builds for just an added layer of protection. Once we had all the short-block parts on hand, we hauled them over to Gray's Automotive Machine in Tigard, Oregon, so they could work their magic. The block was treated to basic high-performance machine work, which includes the installation of main studs, an align hone, a .030-inch overbore, and then honing with a torque plate. The block was then decked just enough to keep the pistons .005-inch down in the cylinder at top dead center. Once the machine work was finished, the block was thoroughly cleaned and then the short-block was assembled.

906 Heads And An MP 557 Camshaft

For the baseline configuration, we used a set of 906 heads we've had around for a few years. These are basic 906 heads with a set of 2.14/1.81-inch valves, and some good quality Comp Cams 939 valvesprings with Comp retainers. They have never been ported, but the bowls were hogged out to match up with the bigger valves. These heads haven't ever seen a flow bench so we don't know how well they flow, but it probably isn't anything fantastic. In other words, these old 906 heads are basically just like countless other cast-iron heads that are bolted on to the average guy's big-block.

To go along with the old-school 906 heads, we slid in a .557-inch lift solid flat-tappet grind from Mopar Performance. The MP 557 is a classic grind that has been around forever, so we thought it would make an excellent baseline camshaft. Our original plan was to test the 557 against some modern camshafts to see just how it compares, but we ran into a time crunch and the only dyno pulls made were with the 557 cam.

To complement the 906 heads, we used an unported Mopar Performance M1 manifold. The M1 manifold is a good choice for this type of smaller street/strip type of motor. While it might not match up with a more modern intake, it seems to work pretty good when combined with a modest flat-tappet cam and a good set of headers. This baseline combination of parts is pretty close to the combination listed in the Mopar Performance catalog as the Super Street 10.90-second engine. The MP recommendation: an RB block with the 557 cam, an M1 manifold, a 750 carb, and 11:1 compression. That is basically the same combination that we built here, but in the smaller B-block and with just a tad less compression.

Dyno Results With 906 Heads

Once the engine was fully assembled, we strapped it to the dyno at Gray's Auto Machine to see just how well the combination worked. Ignition timing was set at 36-degrees advance, and the Holley 750 was jetted to give us an exhaust gas temperature of 1,350 degrees. Once the cam was broken in and the fluid temps brought up to working range, we pulled the lever to see how it would do. The average of three runs gave us a peak torque of 500 lb-ft at 4,800 rpm and a peak power reading of 500 hp at 6,200 rpm. While the 557 cam might be a tad big for street driving, this overall combination should be a great setup for a low maintenance bracket car.

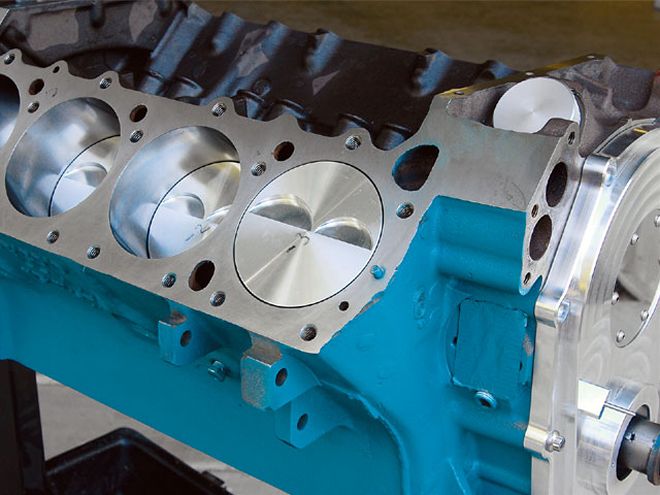

A top view of the short-block shows the Diamond flat-top pistons in position. The block was decked until the pistons were almost flush with the top of the block. we left the slugs .005-inch down in the cylinder. Having the pistons at zero deck puts the compression ratio at 10.0:1 with the Edelbrock heads and a standard .030-inch thick gasket.

A top view of the short-block shows the Diamond flat-top pistons in position. The block was decked until the pistons were almost flush with the top of the block. we left the slugs .005-inch down in the cylinder. Having the pistons at zero deck puts the compression ratio at 10.0:1 with the Edelbrock heads and a standard .030-inch thick gasket.

Switch To Edelbrock Heads, A Victor Intake, And Racer Brown Rocker Arms

The dyno results with the 906 heads were decent for such a simple combination, but we felt the need to bolt-on a few more modern parts in search of even more power. We had a set of Edelbrock aluminum heads that were last used in the Jan. '05 article titled "Manifold Power." The heads had been lightly ported by Dwayne Porter at Porter Racing Heads for that article. After his rework, the heads flowed 290/220 cfm at .600-inch lift. These Edelbrock heads have beehive springs from Competition Cams installed on them, and we installed a set of 1.6/1.5 rocker arms from Racer Brown to pump up the power a little more. While we were at it, we also bolted on a Victor 383 manifold to replace the M1 manifold from the previous tests. The short-block remained identical between the head tests as did the headers, carb, oil system, and ignition.

Since the camshaft has already been broken in, we were able to get right back to testing once the head swap was complete. The head swap was fairly easy to accomplish on the dyno since all of the parts other than the head gaskets were re-used. The Edelbrock heads are stock replacement heads, so the same head bolts, pushrods, rocker arms, and so on will swap directly across.

Once we had the bolts all tight, the little 432 responded by cranking out 507 lb-ft of torque at 5,100 rpm and 545 hp at 6,200 rpm. So the peak torque stayed about the same between the two different heads, but the Edelbrock combination allowed us to carry the torque curve higher for an additional 45 peak horsepower. In a bracket car, that extra power on the top end would be very noticeable, and the reduced weight on the front of the car would just be icing on the cake.

Conclusion...For now

Overall, we're happy with how this little 432-inch motor turned out. These new Diamond Racing pistons seem just the ticket to get some new life out of an older 383 block that might be sitting neglected in the corner. If a person really wanted to make a stock-looking, big-block A-Body, we bet a set of cast-iron heads could be ported to flow well enough to make a real stock-looking powerhouse. If you went down that path you could have a healthy 550 horse big-block that looked stone stock. Now that would be fun!