Even Mopar guys seem to relegate 318 small-blocks to one of two fates: leaving 'em running happily bone-stock in beaters or tossing 'em in the dumpster after an engine swap. Sadly, the most ubiquitous LA engine has always been viewed as the useless punk of the family. At the risk of generalizing, they are almost never built as performance engines.

Introduced in 1967 as a two-barrel engine with a bore and stroke of 3.91x3.31, the 318 was an enlarged version of Chrysler's LA small-block that debuted in 1964 with 273 ci. Their image was soon trampled by the performance 340 in 1968 and later strangled by abysmally low compression and regressive smog equipment. They are rarely considered for a rebuild because performance pistons are hard to come by, and even if they weren't, most small-block Mopar fans faced with the financial hurdle of a total rebuild will spend a few bucks more to pick up a 360 engine core, which are still a dime a dozen.

1 A key problem with 318s is that the pistons are typically well below the deck surface at TDC, making compression ratio a hurdle with the stock slugs. Most guys would rather move to a larger-inch engine if faced with buying new pistons.

1 A key problem with 318s is that the pistons are typically well below the deck surface at TDC, making compression ratio a hurdle with the stock slugs. Most guys would rather move to a larger-inch engine if faced with buying new pistons.

On the other side of the coin, considering the sheer numbers of 318s installed in a variety of body styles, a sizable percentage of entry-level Mopars are found with fine-running 318s between the fenders. Either that or you can find one free for the taking (chances are there's one laying in the street in front of your house right now), making it a prime choice for a Junkyard Jewel buildup.

Now we must consider the paradox of the 318: how to extract proud power while saving nickels and dimes for the preordained engine replacement to follow. The easy thing to do would be to dress our 'teen with aftermarket goodies like a cheerleader headed for the prom, but philosophically and practically, the 318 lends itself more to a bucks-down, workingman's buildup.

The Good News

First, we need to establish clarity here; 318s can run. Though the bore is a little under the "magic" 4.00-inch spec, the bore-to-stroke ratio is actually slightly better than a 350 Chevy's, and there's no refuting that this is the true measure of breathing potential per unit of displacement. With the stock 6.123-inch rods, the 'teen offers a rod ratio the competition would die for (1.85:1). Like all Mopar small-blocks, the valves are inclined at an advantageous 18-degree angle, the realm of older Chevy NASCAR race heads.

The Bad News

Where does the 318 fall over? Stock 318 heads, with the exception of the '78-up four-barrel heads borrowed from the 360, are small-port assemblies with paltry 1.78/1.50-inch valves. Head flow in stock form is poor. Next, typical 318 pistons are of the flattop variety, but are factory-installed at anywhere from 0.050-0.090 inch below the deck at TDC, crippling compression and efficiency. Finally, there's the pipsqueak OE camshaft, with the most common grind lifting the valves a meager 0.373/0.399-inch and only keeping them open with a gross SAE duration of 240/240 degrees. Add two-barrel induction and restrictive iron exhaust manifolds, and it's easy to see why performance has never been the 318's calling card. The factory SAE net rating on stock 318s from '72-'88 varied between 120 and 175 hp.

The Core

Our Jewel 318 is an '84 that we plucked years ago from a 120,000-mile Diplomat cop car, then freshened with new rings and bearings without setting foot in a machine shop, plunked into an A-Body, and hammered through another 100,000 miles of daily use. It served us well, but was ultimately removed in favor of a 340. Despite the taxicab mileage, an inspection revealed a modest bore taper of 0.0015-0.002-inch. There was life in that there short-block, even with well over 200,000 miles on the bores, pistons, and crank. Credit the low bore wear to moly rings all its life (factory equipment in police 318s) and fleet maintenance (at least until we got ahold of it). Rebuild? No, the factory short-block would live on. But we had to prescribe the penance for the three mortal sins of the 318: its frailty in compression, flow, and camshaft.

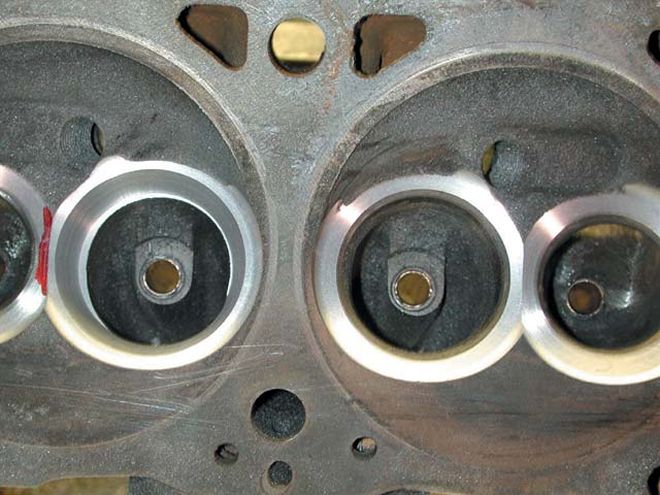

5 Machining the heads for larger valves dramatically increases the diameter of the port throat in the bowl, as seen in the intake port to the left after machining with a 75-degree cutter.

5 Machining the heads for larger valves dramatically increases the diameter of the port throat in the bowl, as seen in the intake port to the left after machining with a 75-degree cutter.

Compression

An inspection revealed the stock pistons to be 0.058 below the uncut factory decks, so the first order of business was to consider the cylinder head possibilities to deliver some compression. With the small cubes and excessive deck clearance, our 318's compression ratio with junkyard 360 heads would fall to the kerosene-burning range of 8.0:1. We needed heads with two criteria: ready availability and small chamber volumes. The '85-and-up swirl-port 318 two-barrel heads (casting number 302) filled the bill on both counts; they come stock with modern, heart-shaped, 59cc chambers and are commonly available on such exotica as '85-'91 318-two-barrel-equipped Chrysler Fifth Avenues, Diplomats, Grand Furys, pickups, and vans. With large, flat Milodon valves filling the chambers, plus a 0.050 cut on the mill, our final chamber volume was reduced to a compact 52cc, bringing the compression ratio to a whisker under 10.0:1 when combined with thin head gaskets from Mopar Performance (PN P4349557).

Cheap Head Flow

The milled No. 302 heads offer compression on the cheap, but fall short on the flow side of the equation. These heads carry the common 318/two-barrel valve sizes of 1.78/1.50-inch and in stock trim flow about 135 cfm stock on the intake side. Our plan was to find flow by porting the heads and upping the valve diameter to 2.02/1.60 with a set of Milodon street valves. The valve spacing on all small-block Mopars is the same, so these valves will fit in the 302 castings the same as with any 318/340/360 heads. Valve shrouding isn't any more of an issue than with other small-block Mopar heads, since as part of the valvejob the chambers were cut concentric to the valve out to near the line of a Fel-Pro gasket. This makes the chamber quite a bit wider than the 318's stock 3.91-inch bore in the area adjacent to the valve. To address this, the bores were chamfered (notched) to minimize shrouding by the shelf left where the chamber meets the bore. Contrary to popular misconception, 2.02-inch intake valves fit the 318's bores without a problem; in fact 2.08-inch intake valves won't hit.

6 The pockets were finished by hand-porting the bowls, profiling the guides, and contouring the all-important shortside turn.

6 The pockets were finished by hand-porting the bowls, profiling the guides, and contouring the all-important shortside turn.

The intake port runners were opened to a 360 gasket size, quite an enlargement from the stock 318 dimension. This move allows the runners to mate nicely with a performance intake manifold (which are typically based on the larger 360 port dimension) or to a stock 360 intake. The exhaust runners were opened to the dimension of a Fel-Pro header gasket. At the other end of the passages, the seat area was prepped with a Serdi-machined cut of the chambers out toward the head gasket line to minimize chamber shrouding of the valve. The oversized seat form was cut, along with a 75-degree bottom cut, which greatly opened the port bowls. After machining, the hand-porting involved blending the machined cuts into the as-cast bowls, streamlining the valveguide bosses, then blending and widening the short turn to a smoothly rolled form from the port floor to the valveseat, eliminating the various factory humps in the corners of the turn. The fully ported No. 302 heads with larger valves installed showed an intake flow improvement of nearly 60 percent to a respectable 215 cfm at a peak of 0.500 lift.

Are these low-buck heads? Getta grinder and learn to use it, and the answer is yes. There's no such thing as a free lunch; sometimes the trade is time and effort for cubic dollars.

Camshaft

With the head dilemma settled, we meditated on camshaft selection. We visualized the grandeur of a roller or solid and the possibilities of impressive high-end power. Such thoughts were abandoned, and clarity came in the form of a street hydraulic cam. Besides the cheaper buy-in for the cam and lifters, a hydraulic stick would allow us to retain our 318's stock, non-adjustable, stamped-steel rockers and factory pushrods. For real dual-purpose street duty, the Comp Xtreme Energy 268 is a sweet cam, with acceptable road manners, and enough eccentricity at 224/230 degrees of duration at 0.050 with a 110-degree lobe separation angle and 0.477/0.480-inch lift to make some power. In a moment of glorious butchery, we installed the cam with a used chain and gearset.

The Extras

All that was required to make our 'teen whole was to endow it with induction and exhaust. Here, we sought to employ the humblest of inductions, a factory iron four-barrel intake from the smog era, resplendent with a factory ThermoQuad (TQ) carburetor. Although devoid of glamour, the factory induction is readily available at charity pricing, and actually works pretty well. At the exit of the ports, we employed four-into-one tube headers with 15/8-inch tubes, supplied by Hooker. The ignition included the same quarter-million-mile Mopar electronic distributor and plug wires that had served our 318 on the road. Even the plugs hadn't seen the light of day in many miles.

10 Skipping a low-rise dual-plane, we went straight to the Edelbrock AirGap two-plane intake simply because we know they really work.

10 Skipping a low-rise dual-plane, we went straight to the Edelbrock AirGap two-plane intake simply because we know they really work.

To the Dyno

We arrived at the Westech dyno facility with what looked like a stock 318 four-barrel engine with headers (which wasn't far from the truth) and filled the guys in with the details. Usually supportive of our efforts, dyno operator Steve Brule was unable to disguise his lack of enthusiasm for our junkyard creation. What should it make? Freiburger weighed in at 320; Brule wasn't expecting 300, while my number of 350 drew looks of skepticism. With the opening pull after warm-up, the 318 delivered 329 hp at 5,400 rpm, then a backup run showed 335 hp at 5,100 rpm. Next we began tuning the TQ, leaning the mixture to find 362 hp, then 368 at 5,600. After more work on the TQ than we care to discuss and a dozen dyno pulls, we reached our best numbers with this combination: 379.3 lb-ft at 4,100 rpm and 375 hp at 6,000 rpm! Stout for any street small-block and enough to puzzle the dyno crew for such a humble-looking 318.

400hp Breathing Apparatus

Even the most jaded of us had to believe that an aftermarket induction would add substantial power. We moved directly to the intake that's consistently the best two-plane we've run: the Edelbrock Performer RPM AirGap. The manifold requires a square-bore carb, unlike our spread-bore T'Quad, so we also employed a budget four-barrel based on a swap-meet Holley 650 double-pumper core with a ProForm main body.

11 A junked Holley 650 double-pumper was made serviceable with a new ProForm main body. It's a nice cheap path to a high-performance carb, and the perfect piece to top the squarebore intake on our 318. We found the supplied jets rich for our purposes, and took them down to 70/76s to find peak power. Note the streamlined air entry of the ProForm center body.

11 A junked Holley 650 double-pumper was made serviceable with a new ProForm main body. It's a nice cheap path to a high-performance carb, and the perfect piece to top the squarebore intake on our 318. We found the supplied jets rich for our purposes, and took them down to 70/76s to find peak power. Note the streamlined air entry of the ProForm center body.

The new induction certainly made our 318 look more the part, and after several jetting changes, netted a wild 394 hp at 6,100 rpm and 403.1 lb-ft at 4,600. We were so close to 400 hp we could taste it. A 1-inch open spacer was positioned under the carb with the intent of putting it over the top. We found on this combination the carb need to be jetted up much more than we normally see with the addition of a spacer, requiring four jet sizes front and back. Once out of a dangerously lean condition, the 318 cracked 401 hp at 6,100 rpm. Revisiting the ignition timing found our best output of the day: 406 hp at 5,900 rpm and 408 lb-ft at 4,700 rpm. Stout numbers for "just" a 318. Interestingly, we found the engine made best output with only 30 degrees of total timing, indicating a very efficient combustion process, akin to the most modern of fast-burn heads.

Wrapping It Up

What we had at the end of the day was a remarkably stout small-block that can be built for chump change if you're willing to do the porting time, yet is docile enough for a daily driver. Address its key shortcomings, and the 'teen can make power that no one would expect. Like we said earlier, 318s are almost never built with real performance in mind, though they can deliver plenty. Therein lies the second paradox of the 318.

11 A junked Holley 650 double-pumper was made serviceable with a new ProForm main body. It's a nice cheap path to a high-performance carb, and the perfect piece to top the squarebore intake on our 318. We found the supplied jets rich for our purposes, and took them down to 70/76s to find peak power. Note the streamlined air entry of the ProForm center body.

Junkyard Jewel 318 Power Curves RPMTEST 1TEST 2TEST 3TorqueHPTorqueHPTorqueHP3,000334.9191.3354.1202.3349.1199.43,500360.7{{{240}}}.4378.2252.0380.7253.74,000376.6286.8402.3306.4401.5305.84,100379.3296.1402.4314.1401.6313.54,500374.0320.4402.5344.9400.1342.84,600374.0327.6403.1353.0400.6350.94,700373.5334.2400.6358.4408.0365.15,000363.9346.4389.7371.0402.0382.75,500344.0360.2368.3385.7386.5404.85,900331.1372.0347.1390.0361.4406.06,000328.3375.0344.0393.0353.8404.26,100319.4371.0339.2394.0347.8404.0

11 A junked Holley 650 double-pumper was made serviceable with a new ProForm main body. It's a nice cheap path to a high-performance carb, and the perfect piece to top the squarebore intake on our 318. We found the supplied jets rich for our purposes, and took them down to 70/76s to find peak power. Note the streamlined air entry of the ProForm center body.

Junkyard Jewel 318 Power Curves RPMTEST 1TEST 2TEST 3TorqueHPTorqueHPTorqueHP3,000334.9191.3354.1202.3349.1199.43,500360.7{{{240}}}.4378.2252.0380.7253.74,000376.6286.8402.3306.4401.5305.84,100379.3296.1402.4314.1401.6313.54,500374.0320.4402.5344.9400.1342.84,600374.0327.6403.1353.0400.6350.94,700373.5334.2400.6358.4408.0365.15,000363.9346.4389.7371.0402.0382.75,500344.0360.2368.3385.7386.5404.85,900331.1372.0347.1390.0361.4406.06,000328.3375.0344.0393.0353.8404.26,100319.4371.0339.2394.0347.8404.0

Test 1: Factory iron smog intake and ThermoQuad carb

Test 2: Edelbrock Performer RPM AirGap intake and ProForm double-pumper carb

Test 3: Add 1-inch open spacer