In gearhead heaven (or maybe it's hell), everybody would drive around with open headers. In the real world, laws and the basic demands of civility dictate we have exhaust systems on our cars. So how do you pick the right pipes for your car? Size? Sound? Whatever the muffler guy feels like installing that day? Maybe, but we tried a more scientific approach and tested a pair of exhaust systems to quantify the difference on our Every Trick in the Book GM Performance Parts ZZ454 crate engine.

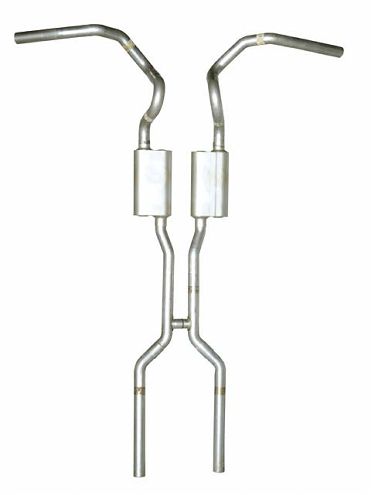

Flowmaster made this test easy for us by cataloging complete 2.5- and 3-inch exhaust systems for '68-'72 GM A-body cars (Chevelles, GTOs, and so on) in its American Thunder line. Each consists of mandrel-bent aluminized exhaust tubing with H-style crossovers, over-the-axle tailpipes, and a choice of mufflers. With both systems, we tested Flowmaster's Super 40 series Delta Flow mufflers, which feature a series of three internal baffles, or deflectors, that reduce interior resonance to produce a quieter sound inside the vehicle. With the 3-inch system, we also tested a set of larger 30 series mufflers with Flowmasters' traditional single-baffle chambers head-to-head against the Delta Flow mufflers.

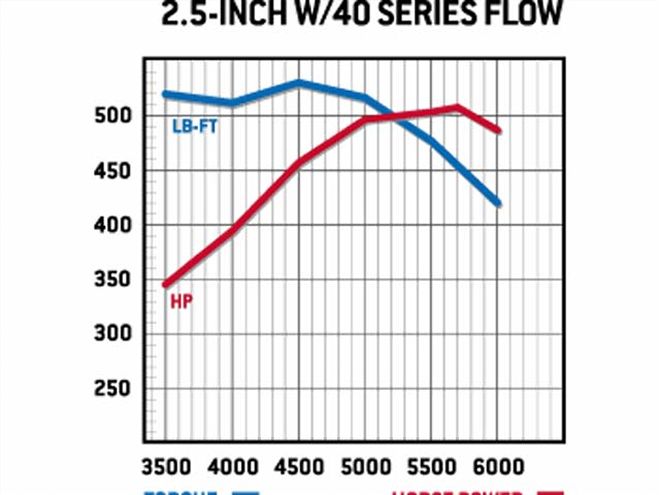

The 3-inch American Thunder system is noticeably bigger, heavier, and louder than the 2.5-inch version, and it takes up slightly more room under the car. It also made more power everywhere in the curve even with this fairly mild 454 big-block.

The 3-inch American Thunder system is noticeably bigger, heavier, and louder than the 2.5-inch version, and it takes up slightly more room under the car. It also made more power everywhere in the curve even with this fairly mild 454 big-block.

In theory, the larger the engine's displacement and the higher the rpm where peak horsepower occurs, the better it should respond to the reduced backpressure of a larger-diameter exhaust. Conversely, it's been said that a mild engine with too much exhaust flow may fall on its face with not enough backpressure, though we've never seen that to be true and can't even imagine how backpressure could help performance in a four-stroke engine.

So it came as no great surprise that our test revealed more power everywhere with the 3-inch system compared to the 2.5-inch system. Although our ZZ454 is relatively mild with its 2-inch-primary Hooker headers and Comp Cams 230/236-at-0.050 hydraulic-roller camshaft, it's still a 450-plus-cube big-block, and it pumps a lot of air to make 520-plus horsepower. On average, compared to the 2.5-inch system, the 3.0-inch system made an additional 13 hp and 15 lb-ft of torque from 3,500 to 6,000 rpm and picked up 14 hp and 18 lb-ft of torque at the peaks to finish with 522 hp at 5,700 rpm and 549 lb-ft at 4,400 rpm. Strike down the myth that the smaller system would favor low-end torque at the expense of high-rpm horsepower--in reality, it was weaker everywhere.

Also interesting is the comparison between the different-diameter exhausts and the open-exhaust configurations we tested last month (see "Header Flog," Oct. '04). In that test, using the same headers and 18-inch collector extensions, horsepower and torque were up 10 hp and 12 lb-ft (see graph) compared to the best run with the full 3-inch system. That's pretty much what we'd expect from the open exhaust. Last month we also proved that running open headers on this engine without collector extensions produced less power, and comparing the results of both rounds of testing shows that the full 3-inch exhaust system was on par with the open headers, which backs up our contention that running open headered (at least without collector extensions) is probably costing you power.

The goal of this Every Trick in the Book series from the start has been to explore many widely held horsepower theories to see if they still hold water, at least with the specific engine we're testing them on. So far we've felled a couple, including the myth that engines make more power without an air filter ("Tune Your Air Filter," Aug. '04) or with open headers ("Header Flog," Oct. '04). This month we added one more.