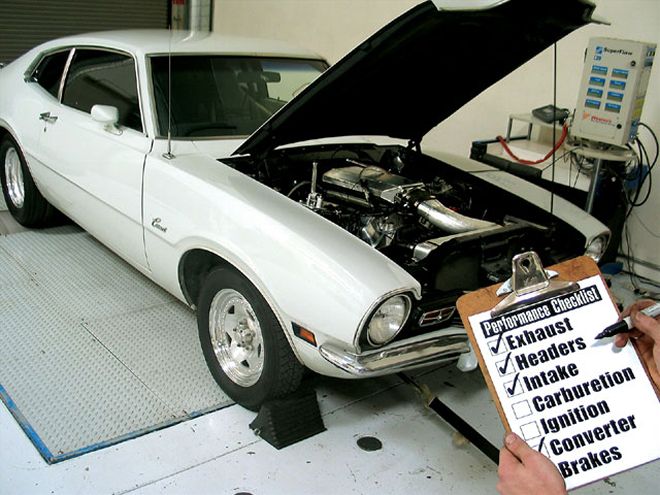

It seems so simple at first: Buy a car, bolt on some goodies, go fast. Yet for some reason, it often doesn't work that way. Either you can't decide where to spend your limited funds, or you actually get to raid the speed shop only to find that the car doesn't respond the way you'd hoped. So what then? Give up? Get a night job to buy more parts? Buy a Honda?

The answers are no, no, and, anything but that! Don't sweat it-we've compiled a basic plan to get you from ground zero to a respectable level of performance without freaking out and not getting inside the engine. It's not specific to any one type of car, but the relevant facts are there-you just have to do some additional research to fill in the specifics for your particular machine.

ExhaustThe very first thing we'd recommend improving on any car or truck would be the exhaust system. This is an area where virtually all production-based cars can stand major improvement. Obviously if you're considering a set of headers you should also upgrade your exhaust system, but exhaust upgrades can benefit cars without headers as well. A hard and fast rule is to always eliminate as much of the exhaust restriction as possible while still retaining decent sound-muffling.

First, the basics: If you're running a V-8 engine in a conventional car through a stock single exhaust and you want to make power throughout the rpm range, you need to go with duals. Even a stock small-block will pick up some power throughout the rpm range with a basic system using a pair of decent performance mufflers. Although it's all the rage to put enormous pipes on musclecars today, most small-blocks from the '60s to the '80s breathed into 2-inch systems, and that's what their manifold outlets are sized for. You can step up to 211/44 if your exhaust guy has skills, and they'll work well later on with headers. A 211/42-inch system from stock manifolds will also work, but they'll work even better when you add headers later on. Also keep in mind that most replacement pipes are compression-bent or "crush-bent," meaning the machine that shapes them can't prevent the inside of the bends from collapsing a bit. This can seriously hinder flow in particularly tight bends by reducing the internal cross-sectional flow area-in essence making them smaller inside.

Fortunately, the aftermarket has greatly expanded its offerings for mandrel-bent systems, so that for most popular (and even not-so-popular) cars you can simply buy a kit. You'll still need to have the muffler shop create pipes to connect to your manifolds, but this may be the excuse you've been searching for to get those headers.

As far as tube sizing, dual 3-inch systems are really intended for healthy big-blocks. The rule of diminishing returns definitely applies to exhaust systems, so the gains you got going from a single system to 211/44-inch duals won't be repeated when your 300hp small-block is blowing into 3-inch pipes with race mufflers. A mandrel-bent 211/42-inch system will be more than enough for most street small-blocks. Also remember that any 3-inch system will be loud-very loud.

Selecting mufflers is difficult since the catalog can't tell you what they sound like, although more and more muffler manufacturers are loading sound bites on their Web sites. Another alternative is to scope out appealing tones at cruise nights and shows, and then inquire with car owners to find out what they're using and how satisfied they are. Remember that high-flow, race-oriented mufflers are loud, and that much of that noise will wind up inside the car with you, often as a maddening resonance.

Most of this applies to late-model vehicles as well, though some of these cars-Camaros and Firebirds in particular and most trucks-have to run single systems. For these situations, a large single pipe can usually provide ample flow; 3-inch F-body after-cat systems are quite common, and 4-inch pipes are also available for hairier combinations. Ditching catalytic converters was the norm in the '70s and '80s, but it really isn't necessary anymore. Even the factory cats from the last decade usually flow so well that they only hinder performance slightly, if at all. Aftermarket cats have shown that even highly modified engines can live with smog controls without major sacrifices. Staying legal no longer equates to low performance.

Headers

One of the classic modifications of hot rodding involves installing tubular exhaust headers in place of the factory cast-iron manifolds. As most of us know, one of the most rudimentary rules of rodding states that the easier it is for the exhaust gases to get out, the more power the engine can make. So, obviously the part of the exhaust system that attaches directly to the engine is the most critical.

Back in the day, choosing headers was fairly simple. You bought a set of full-length tubes that merged with a four-into-one collector and joined the exhaust tubing with a flat flange that used a gasket. Those sorts of headers remain the mainstay of the genre, but you also have to be concerned with primary tube diameter and collector diameter. An alternative to a full-length header is a "shorty" design. Of course, the shorties were initially designed for late-model vehicles where emissions are a concern, so that the catalytic converters and other smog devices could remain intact and in their original locations. In recent years, some header manufacturers have found that a shorter header can be advantageous in a non-smog application, particularly if ground clearance is an issue. Most of these headers are considered 31/44-length, as they're longer than smog-legal shorties, but don't extend all the way to the vehicle's toe-board like a full-length design. Usually, 31/44-length headers position the collector at about a 45-degree angle to the ground, terminating in the area of the oil pan flange. Dyno-testing has shown that despite their abbreviated dimensions, 31/44-length headers can actually make more horsepower than comparable full-length tubes, but often deliver significantly less peak torque.

Which headers you choose will obviously have a lot to do with the car you're building. For late-model stuff that is still subject to smog laws and tests, certified shorty headers with an exemption number are the way to go. For other cars, the intended use is more of an issue. For example, installing a set of full-length tubes with 2-inch primaries and a 4-inch collector on a 300hp small-block for street cruising will prove to be an expensive lesson in overkill. Be realistic about your car's potential and recognize that if you go to the track twice a year, it might not be worth dragging full-competition tubes across every driveway and speed-bump you encounter in your daily travels.

Conversely, if you have a high-compression big-block with a big cam, don't cheap out on the entry-level bargain tubes if you're looking for a significant performance gain.

Intake Manifolds

This is another area that has become far more complicated than it might have been 20 years ago. But the upside is that research and development of aftermarket manifold offerings has taken great strides since the early '80s, so the benefits of upgrading are better than ever.

For the carbureted crowd, this leads us right to the age-old debate over single-plane versus dual-plane. Back in the '70s, some of the aftermarket intake manifold manufacturers tried to bridge the gap between the two by creating street-oriented single-plane intakes, but in recent years, the better option for the street/strip small-block set seems to be track-oriented dual-planes. That may sound like an oxymoron of sorts, but manifolds like Edelbrock's Performer RPM series offer the benefits of low-end power and smooth low-rpm operation typically associated with dual-planes with the added advantage of high-rpm flow characteristics to keep performance engines happy all the way to 6,500 rpm. Dyno testing has shown time and again that these designs work, and the most recent addition of the Edelbrock Air-Gap design, for example, separates the intake runners from the manifold's floor to keep heat from the engine's crankcase away from the intake charge like single-plane intakes have been doing for years.

Of course, the RPM series can only go so far, so when it comes time for a truly healthy engine that will see regular track use, a good high-rise single-plane still makes sense. Modern single-plane intakes are able to support the high-flow capabilities of modern performance cylinder heads, and often minimize the sacrifices to the low-end normally associated with these designs. It seems that 600-plus-hp engines are no longer that uncommon, and while much of this can be attributed to modern cylinder head port technology, a good deal of credit should also go to the intake manifolds that support those killer heads.

We can't ignore fuel-injected performance cars, since this has been the norm from Detroit for nearly 20 years. Plus, the level of performance from late-model cars running engines like GM's LS1 is astounding, particularly when you consider how streetable most can remain. Again, the aftermarket has stepped up to offer improved manifolds for most popular EFI applications, eliminating a major obstacle to ultra-high-performance EFI engines. In fact, there are so many offerings for some of the most popular applications that builders of cars like the 5.0L Mustang have to make careful choices in much the same way carbureted builders do to ensure that they don't over or under do it. The long runners of intake manifolds found on 5.0L Mustangs and TPI Chevys are made that way to take advantage of ram tuning. The length of the runners is specifically sized to coincide with cam timing to take advantage of intake charge pulses so that low-end torque is enhanced. However, these same longer runners usually sacrifice upper-rpm performance. Larger runners often boost output, but short-runner, box-plenum intakes on otherwise stock engines can make for sluggish low-end performance. As usual, the "bigger is better" approach is not advisable for stock or mild engines. Typically, a stock or mild EFI engine that originally had long runners will benefit from a manifold with similar-length runners that feature a larger cross-sectional area for increased flow while maintaining low-rpm velocity. Once you upgrade your heads and cam, you may be ready for something more serious.

Carburetion

For those running carbs, the choices are vast. However, just as with most aspects of your engine, the biggest, baddest aftermarket piece is not going to be the one for your mildly tweaked street cruiser. Stock two-barrel carbs are like running at part-throttle with a real induction setup, and the myths about superior fuel economy have long been proven erroneous. A well-tuned four-barrel will increase performance and economy, but selecting the right carb and setting it up properly seem to be elusive to many novice rodders.

Mild small-blocks really don't need much more than 600-625 cfm. If you have plans for a bigger cam, better heads, and maybe more compression, you might step up to a bigger carb, but be realistic. Your stock 350 will run with a 750 double-pumper, but it might be happier with a 650-cfm carb. Even the larger carb's idle circuit will most likely be rich to the point that no amount of fiddling with the mixture adjustment screws will get it right. An experienced carb wizard could remedy this, but why go through the hassle when what you really need is a smaller unit? Generally, the classic "double-pumper" mechanical secondary carbs are not necessary, nor advisable, for mild small-blocks with automatic transmissions and stock torque converters. You'll just be dumping extra fuel that your engine can't use.

Instead, select from the array of carbs in the 625-to-650-cfm range that use vacuum-actuated secondaries, and start reading up on carb tuning. You may not need to turn a single adjustment screw, but it pays to know what you're dealing with and how to use it.

By the way, if your car already has a four-barrel, or you can get your hands on a factory-type setup to install, don't assume that original equipment can't offer solid performance. Factory quads like the Quadrajet, Thermoquad, and earlier Carter AFB models can all be tuned to support stout street engines.

Ignition

Ignition systems have come a long way since the early days of the musclecar, and many of the factory electronic systems from the mid-'70s are still in favor today. There really isn't any reason to be running breaker points any longer, since they limit the output of the ignition system and require frequent maintenance. Most of the engines we deal with can be retrofitted with a factory-style electronic system from a later model, often using brand-new components either from the OE manufacturer or the aftermarket. A sound alternative is available in the form of electronic conversion kits that can fit into original breaker-point distributors, such as those from Pertronix, Crane, and M&H Electric. The retrofit kits should not be seen as a compromise, as testing has proven their competence. The only possible problem may lie with prior wear to the bushings in the stock distributor.

The quality of your tune-up parts is still a critical issue, even with a strong ignition, and the most commonly faulty element is the spark-plug wires. Even on late-model vehicles where spark plugs seem to last indefinitely, plug wires still deteriorate with use and time. Even a brand-new set of carbon-core resistance wires suffer from high internal resistance. This means less voltage and current at the spark plug and a weaker spark. Resistance testing with an ohmmeter usually reveals the true capabilities of plug wires-look for no more than 100 to 200 ohms per foot as a standard. The best wires are the spiral-wound plug wires from companies like ACCEL, Crane, Moroso, MSD, Taylor, and many others. These are the only plug wires you should consider.

Once you're running electronic ignition through sound equipment, you may want to consider another upgrade to some form of ignition system booster, such as the capacitive discharge units offered by Crane, Jacobs, Mallory, MSD, Pertronix, and others. Some of these companies offer the additional benefit of multi-spark discharge below 3,000 rpm. This means that for every firing of each cylinder, there are actually several sparks to ensure that the mixture lights off completely. Note that while these systems offer real advantages, stock engines won't show as much benefit as more highly modified engines. It all comes back to cylinder pressure. However, once you enter the realm of power-adders, like nitrous and forced induction, a high-output ignition becomes a requirement.

Torque Converters

If your car has an automatic trans, chances are good that you're giving up some quarter-mile performance through that stock torque converter. Most factory-spec converters are designed to stall at a fairly low rpm, usually between 1,500 and 1,800 rpm. This is done to maximize the efficiency by reducing the slippage for a street-driven engine. But the negative effect is that the engine must begin to accelerate the vehicle at well below its torque peak. Aftermarket torque converters are tuned to offer higher-rpm stall speeds, starting just above stock and continuing right on up the tach. This allows the engine to reach its power peak before the drivetrain is loaded and makes for more dramatic launching, which should hopefully translate into quicker 60-foot times, and therefore, quicker e.t.'s.

Stock converters for V-8-powered cars usually measure around 12 inches in diameter, and the mildest aftermarket converters are often based on the same units. However, the more competition-oriented converters are generally smaller, measuring in at 9 or 10 inches. The smaller diameter means less surface area on the internal vanes of the converter, which in turn means that more rpm is required to "lock up" the unit. The added bonus is less rotating mass, which allows the engine to accelerate more quickly. A full-race 9-inch converter with a stall rpm of around 4,500 can launch a properly setup drag car as violently as a side-stepped clutch in a manual trans car, but the converter actually offers an additional benefit of a more cushioned "hit," meaning that the drivetrain is coupled a little less harshly, and that can enhance traction at the drive wheels.

Of course, we once again have to caution against reaching for the full-race stuff for the street. A small-diameter, high-stall converter is always very inefficient at low rpm, which means that when you're cruising down the street, or even on the highway, your converter is slipping significantly. This requires higher engine rpm to maintain cruise speed along with building lots of additional heat in the transmission. Since race converters aren't intended for prolonged use, particularly if it involves low-rpm, the manufacturers aren't typically concerned with this heat buildup, but it will kill your trans in short order if not properly managed on the street. Keep in mind also that the 60-foot capability of the 300hp engine in the car you drive to work, or even the car you occasionally take out from cruising, shouldn't be your primary concern. Street cars can benefit at the strip from converters that stall around 2,200-2,800 rpm without creating too much negative side effect, but an external trans cooler should be considered mandatory.

An added benefit of many late-model vehicles is a lock-up torque converter, which can provide direct drive, much like a manual transmission's clutch, when activated. Transmissions that use this feature, like the GM TH700-R4 and TH200-4R, can be fitted with aftermarket performance lock-up converters that will provide higher stall while maintaining the lock-up feature to enhance the strip performance of street cars without killing fuel economy.

Brakes

Conversations regarding improved braking used to be an afterthought when discussing classic musclecars. Fortunately, the popularity of Pro Touring-style cars has brought brake upgrades to the forefront for many car crafters. What's more, these upgrades are no longer limited to assembling factory-style front discs on '60s-era cars. Instead, those same cars can often be retrofitted with modern high-performance brakes at all corners. In fact, even late-model vehicles can often be treated to upgraded braking thanks to a hearty aftermarket for stopping hardware.

Where you start will obviously depend on what you're driving, and what type of brakes it already has. If you're one of those guys still cruising around with four-wheel drums and a single-circuit master cylinder, you won't believe the difference a properly designed and installed front disc brake system can make. For some cars, front discs were optional and can often be retrofitted either with used parts or with new hardware from aftermarket suppliers like Master Power Brakes or Stainless Steel Brakes. Some vehicles were never offered with discs, but for many of the popular applications, retro-fit disc kits are also available. But you may want to skip over the stock '70s-era stuff and go for something a little more contemporary-like the PBR-based systems offered by Baer Racing for many classics and musclecars. Wilwood offers its own version of updated braking with four-piston aluminum calipers and lightweight rotors as well.

Maybe you drive a fourth-gen Camaro or late-model Mustang GT. Both came with very capable four-wheel discs from the factory, but both could be even better. Again, the aftermarket can help to take braking to the next level. Don't overlook the potential improvements just from higher-quality rotors and high-performance pads.

For any of the vehicles mentioned, it should be noted that very often, modern high-performance brakes will require large-diameter wheel/tire combos to clear the hardware. For example, if you install a 13-inch brake kit on the front of your '69 Camaro, don't expect to bolt the 15-inch Rally wheels back on. Depending on the parts used, even 16-inchers may not fit. This can also affect the kind of rear tire and wheel package for dragstrip use as well, necessitating a 16-inch rear wheel and tire for dragstrip jaunts. So once again, research is vital to the success of the project prior to making any purchases. Keep in mind also that full-race brake pads are really not advisable for street use, as the hardcore stuff typically requires a certain level of heat to function. This means that at low temps, there may be little friction, and therefore, little braking. Trust us, it'll make you pucker if you're not prepared. Be real about the use of your car, and remember that there's no shame in swapping pads in the pits at the road course-in fact, it's pretty typical.