A fender might frustrate you and a quarter-panel may leave you in a quandary, but you can probably build a hood for your hot rod. Believe it; builders with far fewer resources than you and I have made their own special fitting hoods ever since they found ways to make the stock one not fit.

Ken Crawford was one of those early examples. Just after V-J day, he built a Deuce roadster for lakes racing. He channeled the car to improve its aerodynamics, which required him to move the radiator forward. As a result, the original clamshell hood no longer properly spanned the gap between the cowl and grille shell. Being a racer, he did what racers do: he scared up some materials and made his own. After all, there was nobody there to tell him he couldn't.

Mike Longley began by aligning the grille to the car. As the stock grille support rods would've interfered with the coolant hoses if not the induction system he also replicated the setup that the car wore more than half a century ago.

Mike Longley began by aligning the grille to the car. As the stock grille support rods would've interfered with the coolant hoses if not the induction system he also replicated the setup that the car wore more than half a century ago.

Recently Crawford's old Deuce resurfaced, only this time without a lot of what made it unique-the hood for one. Since the car's resurrection was supposed to reflect the way it was when Crawford made history with it, the job required a faithful recreation of that hood. Longley Restorations in Deland, Florida, obliged.

The process the Longleys employed reflects the way pioneers like Crawford crafted their machines. In the absence of the hot rod and restoration shops we now take for granted, those enterprising racers employed resources not necessarily associated with the auto industry. We don't know exactly what resources Crawford used to make his hood but the Longleys used a local sheetmetal shop-a shop that makes ventilation systems specifically. It's an option that Crawford literally could have used in his day had he lived nearby: Jacob Sheet Metal Works has been around for nearly 90 years.

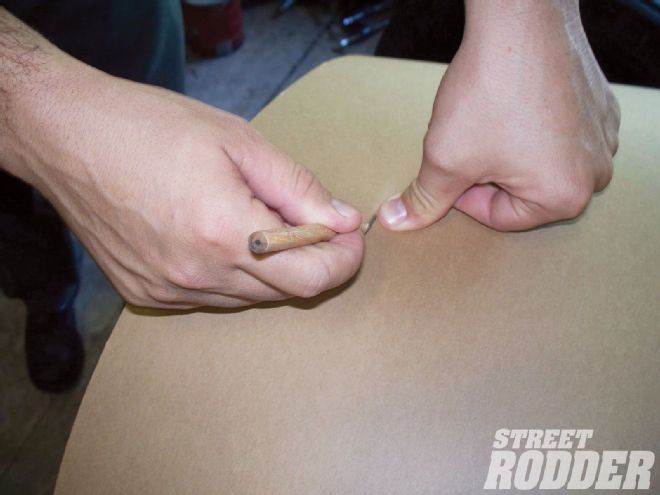

With the grille aligned sufficiently, Longley draped a sheet of chipboard over the top of the cowl and grille shell. He established the first reference points by pressing the cardboard over the grille shell bead at the top and sides and marking their location.

With the grille aligned sufficiently, Longley draped a sheet of chipboard over the top of the cowl and grille shell. He established the first reference points by pressing the cardboard over the grille shell bead at the top and sides and marking their location.

A few caveats before we begin. First, the construction method best suits cars with straight hood-top sides. In Ford terms, that's everything from Henry's first car to the '32 passenger car and the '37 pickup. The compound curve in the leading edges of the vehicles that followed requires more sophisticated tooling and considerably more work.

Second, this method doesn't accommodate character lines as found on cars and trucks from '30 onward. Some bead rolling prior to forming the hood flange would make it possible but that's beyond the scope of this story. Not that the absence of that line mattered to racers of the day; a car's looks didn't make it go any faster, which inspired a stripped-down, purposeful aesthetic all its own.

He then connected those reference points with a flexible straightedge. Once finished, he trimmed along that line.

He then connected those reference points with a flexible straightedge. Once finished, he trimmed along that line.

Sure this method has a few compromises, but what doesn't? If nothing else, the process redeems itself by its simplicity, affordability, and, most of all, authenticity. And chances are, you can do it yourself.