Lead is a mysterious medieval substance. As used in bodywork, lead is revered by tradition but regarded as the dwindling domain of weary sages and old-world diehards. Leadloading has been all but forgotten by the unleaded generation, as modern plastic body-fillers have become the standard fare. The truth is, both have a place in the car crafter's toolbox, each having its advantages in a given application.

Plastic is at its best as a thin glaze over a repaired area. Where lead truly shines is in applications in which its structural strength, superior bond to the base metal, and lack of porosity are used to an advantage.

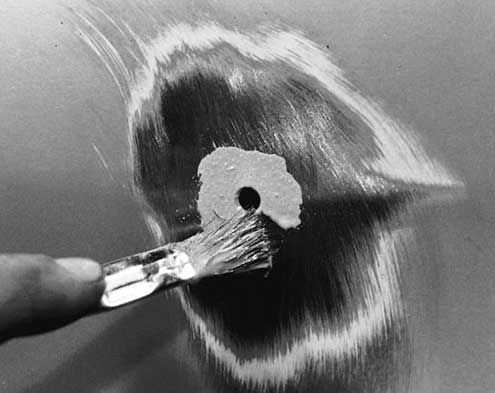

Lead, or body solder, is typically an alloy of tin and lead (usually a 30/70 mix, respectively) similar to the solders used on radiators and in electrical work. What aren't as familiar are the techniques employed when body solder is used. Far from requiring years of old-world apprenticeship, dabbling in lead dabbing can be quickly mastered by anyone familiar with handling a torch. Uses for lead in body repair can run from seam sealing to metal-finishing panel repairs to filling various body holes. The latter is the most relevant application for the neophyte metal fan and fortunately one of the easiest techniques to master.

Our saga began with a 1970 Dart Swinger 340. Removing the optional body side-moulding, we were faced with 48 1/4-inch holes riddling the delicate midsection of the virgin sheetmetal. Welding or brazing the hole is a high-heat process that would invariably creates some panel distortion, and stuffing holes with plastic filler is an inferior repair, temporary at best. Lead offered the only real choice. The accompanying photos detail the metal mayhem, proving that with a bit of old-time alchemy, even an uncouth tech writer can be transformed into a metal master