The Turbo 400 is the strongest of the GM three-speed automatics, but there are several tricks that can improve its reliability.

The Turbo 400 is the strongest of the GM three-speed automatics, but there are several tricks that can improve its reliability.

There are few things in the world of high-performance cars that are truly reliable. One would have to be the GM TH400 automatic. As durable as this three-speed juicebox is, there is still room for improvement. When the Turbo 400 in Greg Smith's 11-second '55 Chevy lost Second gear (see "Speed Tune Your Street Machine," July '06), we took it to consummate automatic-transmission guru John Kilgore for a rehash. Many of Kilgore's ideas are budget based and can be applied to any street-driven or street/strip Turbo 400 trans.

Electric Wot

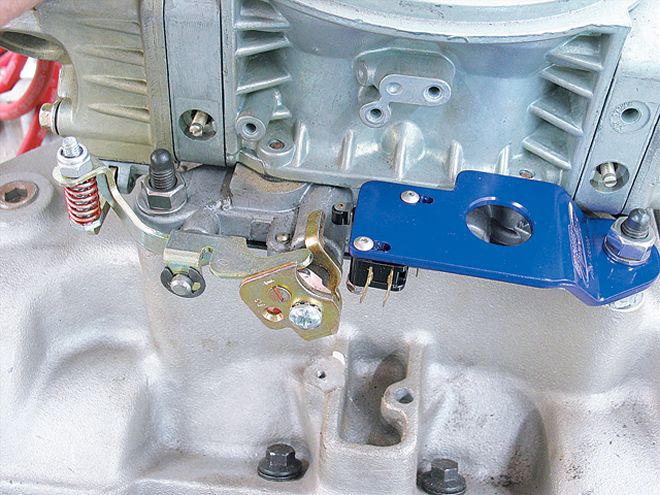

When the Turbo 400 was new, GM engineers decided to employ an electric "kick-down" function instead of the classic rod or cable to signal wide-open throttle (WOT) to the transmission. The factory system uses an electric trigger installed on the carburetor that sends a 12-volt signal to the transmission. With trans swaps, this simple point is often overlooked. The clue that this circuit is necessary is when the TH400 does not downshift from Third to Second at WOT at a speed of around 40 mph, for example. If you have installed a Turbo 400 in place of a Powerglide or a Turbo 350, you will need to install an electric WOT trigger switch. The easiest and perhaps least expensive way is to install a micro-switch on the carburetor that will complete a circuit only when the linkage achieves WOT. The wiring is simple; run one lead from switched battery power to the micro-switch and then from the switch down to the small male terminal on the driver side of the transmission. Applying 12 volts to the trans increases line pressure and commands WOT upshifts to be dictated by the weights and springs in the governor.

A micro-switch on the carburetor triggered only at WOT increases line pressure to the trans, which increases shift harshness and shift points.

A micro-switch on the carburetor triggered only at WOT increases line pressure to the trans, which increases shift harshness and shift points.

How 'Bout a Refill?

One of the problems with any automatic transmission is the oil level in the pan. Overfilling any automatic is bad because the rotating components will whip the oil into foam, which causes all kinds of problems, since automatics operate on the hydraulic principle of an incompressible fluid. Equally as bad is a low fluid level, especially for Turbo 400s.

Kilgore came up with a very simple solution to this dilemma after witnessing multiple oil-level-related trans problems. Kilgore integrates an oil-fill standpipe into the oil pan's drain plug. Anytime the fluid is drained, the refill procedure is to add ATF until oil begins to dribble out of the tube. With the engine running, shift the trans through Reverse and Drive a couple of times to ensure the converter and valvebody both are properly filled. Check the level again and fill until oil dribbles out the standpipe again. Then the pipe is plugged and you're ready to race.

This is the innovative standpipe idea incorporated into Kilgore's standard deep-sump cast-aluminum Turbo 400 oil pan. The proper oil level is equal to the height of the standpipe.

This is the innovative standpipe idea incorporated into Kilgore's standard deep-sump cast-aluminum Turbo 400 oil pan. The proper oil level is equal to the height of the standpipe.

Burnout Blues

Turbo 350s and 400s are the only automatic transmissions that use a sprag to hold Second gear. The sprag is a one-way roller clutch that is responsible for holding the high-gear drum in Second gear. It is also especially susceptible to failure. When the sprag fails, the trans loses Second gear, which is what happened to Greg Smith's '55 Chevy during our tuning session.

Kilgore reports the burnout procedure is usually the culprit for failed sprags. "Guys hit the throttle hard in First gear during the burnout. This rattles the tires at the same time they shift into Second, and that's what kills the sprag." Kilgore also said, "The sprag does all the work to stop the high-gear drum and accelerate the car, so the key is to minimize the shock load to the sprag." Examining the sprag in Smith's trans revealed it to be off center on the high-gear drum, which placed all the load on roughly four to five of the elements (there are 34 total).

The solution, according to Kilgore and several other transmission people we talked to, is to modify the burnout procedure. In Smith's case, Kilgore modified the Turbo 400 for a manual valvebody and instructed Smith to always do his burnouts in Second gear. This prevents a gear-change hit from hammering the sprag and rolling it over during the burnout. With an automatic valvebody, the best routine would be to gently start the tires spinning and quickly shift into Second gear before using heavy throttle to heat the tires.

The Turbo 400 power path is from the input shaft (A) through the forward drum (B) and into the high-gear drum (C). The high-gear drum spins backward at 82 percent of engine speed in low gear, stops spinning in Second gear, and must accelerate up to full engine speed in Third gear.

The Turbo 400 power path is from the input shaft (A) through the forward drum (B) and into the high-gear drum (C). The high-gear drum spins backward at 82 percent of engine speed in low gear, stops spinning in Second gear, and must accelerate up to full engine speed in Third gear.

The Power Path

One key to making a Turbo 400 live is understanding the path the power takes through the transmission. Kilgore laid the big components out, and the information is well worth remembering. Let's assume the torque converter and the input shaft are both spinning at an engine speed of 6,000 rpm. The forward drum weighs 12 pounds and is splined to the input so it also spins at 6,000. The high-gear drum is next in line and weighs even more, at 13.5 pounds. In First gear, it spins at 82 percent of engine speed (for our example of 6,000, that means 4,920 rpm) in the opposite direction. That's a lot of weight spinning in opposite directions, which tends to absorb power. When Second gear is selected, the high-gear drum stops. When Third gear is selected, the high-gear drum must immediately accelerate to engine speed. This means the internal clutches are heavily loaded at the gear change because they must accelerate that heavy high-gear drum up to speed as quickly as possible. This is why the First-to-Second gear change generally feels harsher than the Second-to-Third upshift.

According to Kilgore, "The high-gear clutch pack is the key to making a Turbo 400 live." One key is to prevent high-impact loads from First to Second gear that shock and hurt the sprag. The sprag (also known as an overrunning clutch) is what keeps the drum from spinning in Second gear. Because the high-gear drum is so massive, higher line pressure helps the high-gear clutch pack survive the task of accelerating the high-gear drum up to speed as quickly as possible.

It seems logical that a lighter-weight high-gear drum would be a good idea-which is true when building a race-only trans. But for the street, aluminum drums will quickly wear and cause other problems. Kilgore's solution is a complete change in the Turbo 400's power path along with drastically lighter components (see the sidebar on Kilgore's SuperLite 400).

Performance Building the Turbo 400

Kilgore has been massaging the classic Turbo 400 for well over two decades and has developed several important modifications that not only improve longevity, but also reduce parasitic power losses. Here are a few things we learned watching him assemble Greg Smith's TH400 trans.

Kilgore drills a 0.060-inch-diameter hole in the high-gear drum to vent the drum of oil in low gear, when some oil may be trapped in the drum that might tend to lightly apply the clutches. This would create unnecessary drag. This vent hole is small enough that it does not affect clutch apply in Third gear.

Kilgore drills a 0.060-inch-diameter hole in the high-gear drum to vent the drum of oil in low gear, when some oil may be trapped in the drum that might tend to lightly apply the clutches. This would create unnecessary drag. This vent hole is small enough that it does not affect clutch apply in Third gear.

The Kilgore SuperLite TH400

While the Turbo 400 is a great trans, it's also the heaviest of the GM three-speed automatics. As we saw in the Power Path sidebar, it suffers from extremely heavy rotating components. After years of dealing with these heavy pieces, Kilgore decided to develop what he calls the Kilgore SuperLite TH400. The key to this venture is combining the forward and direct clutch assemblies into one very light housing. The weight differential is an amazing 30-plus pounds of rotating mass that also reduces the overall weight of the trans by the same amount. Along with this reduction in weight, Kilgore offers several First-gear options ranging from 2.10 to 3.00.

While this trans can be used on the street, its real objective is trimming anywhere from 0.20 to 0.50 second off the e.t. on a serious drag car by reducing the power required to accelerate the lighter rotating components. This does come at a price, with the basic SuperLite 400 costing $4,495, but if you're into low e.t. by reducing rotating weight, here's your ticket.