Don’t worry, we don’t expect you to fully understand what dorifto (do-reef-toh) means. It’s not even that hard to comprehend, but to actually do it is a skill. Not everyone can do it, and you’re gonna have to accept that it’s only for a select few. We’re not even gonna tell you where you can do it, but if you have to, please keep it on a closed track. In fact, you will crash your car. Hence, the reason you should only try it on a closed course and never on a public road. It’s drifting: Japan’s underground sport of maneuvering a car to get sideways.

What is drifting? Well, it’s derived from a motorsport well known around the world as rally racing. In rally racing, participants “drift,” or slide, around corners throughout a variety of road conditions: dirt, mud, and snow. They are able to maintain a high speed throughout the turn, as opposed to slowing down and taking the corner slowly. This style of cutting corners eventually found its way to the pavement and was made extremely popular by Keiichi Tsuchiya (Kay-ee-chee Su-chee-yah), aka Dorikin (Drift King). Drifting today is a unique subculture within the Japanese racing scene, and a great majority of those who actually do it are in their early 20s. There are competitions held by Options 2 (Japan’s leading aftermarket enthusiast publication) at various racetracks across Japan, and weekend midnight runs are not uncommon at certain mountain passes, where packs of drifters come to play.

There are three different methods used in drifting. The first technique is side braking, where by pulling the side-brake (commonly known as the e-brake), you’ll lose traction, which allows you to drift. Another method is the stutter cut, which works best when performed in the rain. By cutting slightly toward the opposite direction of the oncoming turn and then cutting hard back into the turn, you cause your tires to slip and lose traction. Clutching is also widely used when you come to the turn. Press down on the clutch and rev the engine, then release (pop) the clutch to break the rear tires loose, therefore causing a loss of traction.

Choosing the Right Platform

Not every car is suited for drifting. You can’t take Mom’s Cadillac and expect it to perform miracles. Most choose to use an FR (front engine, rear-wheel-drive) platform because you can go through a series of drifts that an FF (front engine, front-wheel-drive) cannot perform. An FR will always have power coming from the rear to keep the car sliding, while the front wheels control the drift. With an FF, the front wheels are always in control and powering at the same time. Therefore, you can’t take as many turns, and your car “slides” instead of drifts. You’ll rarely see an FF drifting in Japan as opposed to the number of FRs that are used. FFs are much more suited for touge (toh-geh), mountain runs (literal translation is “mountain pass”), or track racing, but that’s not to say that FRs aren’t used in touge either (they are actually used quite often). This kind of racing puts your car’s handling to the test, focusing more on driver skill as opposed to how a turn is slid through.

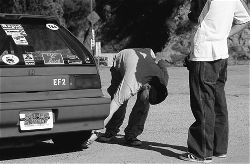

Here is a list of popular drift cars in Japan and their U.S. counterparts. The most popular drift cars are the AE86, aka Hachi-Roku (ha-chee roh-koo; eighty-six), the Silvia S13/S14/S15, and the 180SX/Sil-Eighty. The AE86 is popular because it’s cheap, durable, and is RWD. They are equipped with the 130hp 4AG motor and can be modified easily. Most of the Hachi-Rokus in Japan are almost always beaten on, something commonly associated with drift cars. Drifters are proud to show off these “battle scars” and will tell you a host of stories to go along with them. The AE86 isn’t the most powerful drift car, but because it’s so affordable to buy and build, it remains the top choice to go drifting with.

The best all around drift cars are the Nissan Silvia S13/S14 and the Nissan 180SX/Sil-Eighty. Being just as affordable as the AE86, they have changed little since their introduction. Throughout the years, these cars have maintained the same engines and differed only by body trim and style. The Silvia S13 was released in three versions from ’88–’90: J’s, Q’s, and K’s. The J’s version is the base model (no power options) and is powered by either a non-turbo CA18DE or SR20DE motor. The Q’s is a mid-grade model, but is again powered by either a non-turbo CA18DE or SR20DE motor. The granddaddy of the group is the top-of-the-line K’s model. Fully loaded, it is powered by a 200hp CA18DET turbo motor. Later on, the ’90–’93 K’s came equipped with a 205hp SR20DET turbo motor. Unfortunately, like most of the cars we receive from the manufacturers, we get the tamer versions, such as the 240SX. Besides having a 2.4L KA24DE truck motor and pop-up headlights, our versions are just as cool when compared to the JDM version, right? Don’t think so.

Another variation of the S13 is the 180SX, more specifically the RPS13. It’s the hatchback version and has a perfect front-to-rear weight ratio and a turbocharged SR20DET engine. This car is still immensely popular today because the S13 Silvia went out of production in 1992, while the 180SX is currently still being produced. It is the second most popular drift car after the Toyota AE86. Nissan also released a hybrid of the 180SX and the S13, the Sil-Eighty. It’s a combination of the two with either a S13 front end and a 180SX rear, or vice versa. These are also powered by either a non-turboor turbo SR20DE motor.

The Silvia S14 is really cool, just like this month’s cover car. This car is perfect for high-speed runs and tackling the hardest drifts. These, unlike the S13, come in two versions—the Q’s and K’s. The Q’s is (you guessed it) the lower model and comes with the SR20DE that puts out 160 hp. The all-mighty K’s version features an intercooled, turbocharged SR20DET motor that dumps out 215 hp. S14s can be modified extensively without spending much and could possibly whoop a Skyline’s ass. For someone whose budget is limited, the S14 can be had for roughly $10K used and will give higher-end vehicles a run for their money.

How to Setup a Proper Drift Car

You can’t take the same mentality as drag racing and apply it here. Having a lot of horsepower is good, but your engine should be built more for torque. Not a whole lot, but you’ll need enough to keep your tires spinning throughout the drift. Let’s go over the basics for setting up your car for drift.

We’re assuming you’re living in the U.S., and most of the popular drift cars that you can buy here aren’t as well-equipped from the start as they are in Japan. And that means you have a naturally aspirated car. You’ll want to increase the amount of air coming into a naturally aspirated motor, and the best way to do that is to use an aftermarket intake system of some sort. Choose an exhaust that not only has an increased pipe diameter, but is also designed so you will not lose any backpressure. A loss in backpressure will result in a loss of torque, so you don’t want to pick an exhaust that is too big. Cams are also a good choice because certain grinds or new billets can increase torque, but you should be willing to pay the price for high-performance cams because they won’t be cheap.

Now if you do put a turbo kit on, or if you are willing to or have already installed an SR20DET motor, then choosing the right turbine is key. Research and find a turbine that doesn’t take long to spool up. A turbine that spools faster is good because you can break your traction much quicker. You will put a lot of wear and tear on your clutch, especially if you drift with the clutching style. To prevent any damage to your stock transmission, it would be beneficial to upgrade your clutch and flywheel to stronger aftermarket pieces. These kinds of modifications will aid in transferring the power to the wheels much more efficiently without putting too much strain on the rest of the tranny.

The most important powertrain modification that you can do is to install a limited-slip differential. Most passenger vehicles, and the ones that you will use to drift, run on an open diff that only puts the power to the wheel that has less grip, which is useless until the car is out of the turn. This is where an LSD comes in handy and works by taking power from the wheel that has better grip and biasing it to the wheel with less grip. This is extremely beneficial because as you’re accelerating out of a turn, the LSD puts power to the outside wheel while reducing inside wheelspin. This allows the vehicle to gather speed earlier and exit the turn at a higher speed. There are two types of LSDs: 1.5-way and 2-way. A 1.5-way LSD works only when you accelerate but has little effect when braking. A 2-way LSD is active when you are either accelerating or braking, so this is a more viable option for drifting.

Your suspension setup is also vital, and you have to make sure that it’s stiff. Not a Jenna Jameson kind of stiff, but, well, you know. For both FF and FR you need to use a stiff set of springs matched with the proper dampers like the ones found in a coilover system. A stiff suspension will allow the rear tires to spin a lot easier, whereas a stock suspension will experience body roll, and that makes it harder to spin the rear tires. A stress bar is good for an FR in the rear only because it will help reduce body roll and reinforce weak chassis points.

An FF needs more body roll in order to complete a drift successfully and should be stiffened up front. It needs more momentum and oversteer to roll correctly. You can adjust the toe in/toe out on an FF to 10 degrees on the rear and 5 degrees on the front for good tire/surface contact. A rollbar is an absolute must for FFs and FRs, not only for the safety factor, but also for chassis stiffening. Camber kits/pillow mount plates will help because you can adjust the degree of negative camber needed to give you more stability.

Negative camber causes the tire to tip inward, so when it’s rolling over, it flattens out and has a greater contact patch to the ground. Your wheels should be lightweight (RS Watanabes, Advan, or SSR Reverse Mesh are popular drift wheels in Japan) and something that you don’t mind getting thrashed on. The rear tires should be cheapies, and the fronts should be a set that can last awhile. You’re guaranteed to go through many sets of tires on the rear, so don’t spend too much money; get a pair of used tires instead. Many drifters bring an extra pair of wheels with tires mounted on them already so that they can swap them in when it’s time to go drifting and swap them back out once it’s time to go home. This way, you won’t sacrifice a good set of tires and wheels to the risk of blowing out or getting curb-checked, and afterwards you can roll on the good wheels/tires again.

Drifting isn’t a very popular motorsport and probably won’t be for a few years to come. Just remember, the next time you’re out waiting in sweltering heat for a two-hour tech inspection line to hit the 1,320, someone on the other side of the world has crashed his FC3S into a grassy ditch and is thinking to himself: “Sh—, I knew I shoulda gone drag racing instead.” Stay sideways.