| Project Norad Toyota Celica Part 6 - The Chassis Game

| Project Norad Toyota Celica Part 6 - The Chassis Game

When Christian Rado first approached Bob Norwood about creating a new, ground-breaking Pro FWD Toyota Celica, Norwood had already given such a project a great deal of thought. The FWD Class rules allowed for a certain amount of innovation, and Norwood had some new approaches he was eager to put into practice.

With the project given the green light by Rado, Norwood started brainstorming with his engineers and the car started taking shape. One of the key areas for Norwood to put his radical thinking into practice was the chassis and, in typical Norwood fashion, the 2004 NORAD Toyota Celica is a radical departure from anything that has been constructed to date.

Starting with a clean sheet Norwood had several aspects of the car to consider before he started bending and welding tubes.

"We had to come up with a design that was within the structure of the rules and would still allow us to introduce some new approaches to FWD drag racing design." Norwood explained. "My first consideration was suspension design. I really felt that a lot of traction could be gained by utilizing a true four-link suspension at the front and it would also allow me to integrate a pro-stock 9-inch Ford rear-end. This will allow us to adjust the traction characteristics of the car and also give us a bulletproof final-drive assembly. At the rear, I wanted to use massive tunnel to give the car aerodynamic stability and this would dictate the suspension design to a certain degree. I also wanted the car to be as rigid as possible; I'm still amazed at the amount of flex in some of the cars that are competing in our class."

The huge 16-inch front slicks meant the front section of the chassis would have to be narrow to allow for the steering axis and as a consideration to the crew in the light of minimal service time between rounds Norwood also wanted the engine and transmission to be serviceable in situ and easily changeable in the event of a total failure.

"Drag racing is hard on parts and the easier it is to service the car the better." Norwood, master of understatement, explained. The chassis also had to be SFI 25.1E certified; unfortunately for Norwood, this meant that the original plan to utilize a center-drive position had to be ditched as there are no SFI specs for a center-drive full-bodied chassis.

"I was a little disappointed to say the least," Norwood said. "I really feel a center drive position would be far safer and would also allow for better driver visibility. In the end we have no choice but to comply with the existing regulations but this is something that I think needs to be re-thought."

The rules also dictated other facets of the cars design. The wheelbase of the car has to be within six inches of the stock chassis. In the case of the NORAD Celica this means that the wheelbase will be stretched to 108.3" for maximum stability.

Ground clearance must be a minimum of three inches to a point twelve-inches behind the centerline of the front wheels. Rearward of that point, the ground clearance must be a minimum of two-inches. In the interest of maximizing the aerodynamic properties of the NORAD Celica, the chassis was designed to comply to this rule with millimeters to spare.

The final consideration for Norwood's design team was the weight of the car and as we will reveal, extraordinary lengths would be called for in an effort to get the weight of the race-ready car as close as possible to the 1,650-pound minimum.

As with every other aspect of the car's construction, the team started by outlining the requirements of the rules on paper. Then the ideas the team wants to include are added and a heated discussion invariably follows in which the engineers involved in the project figure out what is realistic and how it will be done.

"We are really lucky [with] this team," Norwood boasts. "We have got some talented people on board and they all have input into what we're doing. Tony Palo is a great fabricator and race engineer with a lot of experience on front-wheel-drive cars. Sean Fischer is our physics guru and is normally responsible for figuring out if some of our more way-out ideas can be made a reality. The enthusiasm of the youngsters and my years of figuring out how to go fast is a great combination. Our team is really a team in every sense of the word, but sometimes I have to pull rank and make a final decision, otherwise, we'd end up talking about it for weeks without getting any work done."

A visit to the Norwood facility in rural Texas reveals just how much thought is given to the design and construction of the car. The shop walls are made from white-board material and are covered in engineering drawings, mathematical formulae and notes on the design. Every day at the shop starts with a discussion on what needs to be done, who will do it and how it will be carried out. Any new ideas are discussed and drawn out on the walls. Democracy in action is a beautiful thing, indeed.

The starting point for the construction of the chassis was the fabrication of a custom "chassis jig." Manufactured from massive steel beams, the chassis jig provides a perfectly true base on which to start welding tubes together.

The base of the jig represents ground-level, and custom clamps were machined and welded on at the relevant points to dictate ground clearance and locate the main tubes. Next, Norwood positioned the engine block and transmission assembly and marked the wheelbase, width and other crucial measurements on the jig. Finally, the long task of manufacturing a state-of-the-art chassis was under way.

The first tubes to be positioned were the front cross-tube and the bulkhead cross-tube. Next, the tubes that run on either side of the engine were cut and positioned; from this point on, the chassis started to resemble a racecar in record time.

All of the tubing is 4130 chrome-moly and with half an eye on the minimum weight rules all areas that aren't structural, load bearing or dictated by the SFI specs are manufactured of the lightest tubing possible.

Of course, designing and constructing a state-of-the-art chassis is never a matter of just welding tubes together in a random fashion. Norwood's team had access to several high-tech modeling and stress analysis computer programs to back-up the years of hands-on experience in the team.

"We have really made an effort to take the guesswork out of the process." Physics guru, Shaun Fischer, explained. "The technology available these days enables us to design parts that are lighter, stronger and more efficient. Most of the main components of the car have been carefully analyzed on the computer before we ever start to fabricate them. A perfect example of this is the rear swing-arm assembly. We had an idea what we wanted but once the stress analysis was completed, we discovered we could save a significant amount of weight and make the part stronger by pressing chamfered holes into the sheetmetal. We had to buy some special tooling to do the job properly, but in the end, we really want to leave as little as possible on the table."

Once the basic structure of the chassis was completed, Norwood's next step was to get Christian Rado on a plane from Pennsylvania for a first fitting. If this sounds like Rado is getting measured for a custom suit, then it's a statement that's not too far from the truth.

"We started by getting the seat position where we needed it and then we custom-fitted everything else around Christian." Team fabricator Tony Palo explained. "It's crucial that Christian feels 100 percent comfortable and all of the controls need to fall readily to hand, especially the safety equipment such as the parachute release and the fire-extinguisher system. The steering wheel, pedals and shift button positions were all dictated by Christian."

Once Christian was measured and the fitting process was complete, the team concentrated on keeping the center of gravity as low as possible to minimize weight transfer and enhance traction.

"We have concentrated on keeping weight to an absolute minimum by using lightweight materials such as titanium and carbon-fiber as much as possible," said Norwood. "Any weight we have to carry, we try to position as low as possible."

A perfect example of this is the floor-mounted Tilton engineering pedal assembly. It weighs the same as a normal pedal assembly but the bulk of the weight is placed close to the floor. It's probably moved the center of gravity by a minute degree, but when you add it all up, the lower center of gravity will make a difference to the car's performance.

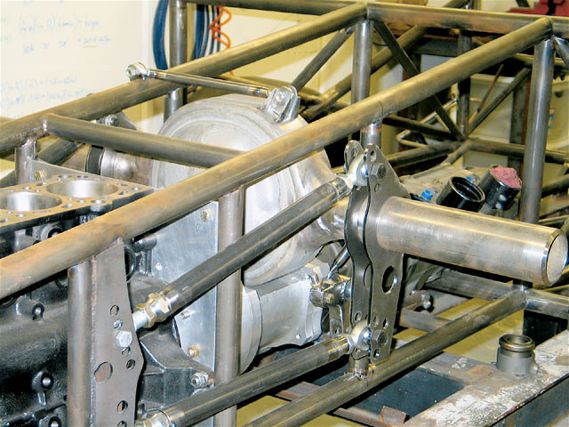

Another example is the positioning of the Penske front shock absorbers. The shocks are laid parallel to the ground under the front axle and are actuated by a custom-built set of rocker arms. To further decrease the weight, a set of custom-wound Titanium springs were manufactured by the Renton Coil Spring Company to NORAD specs.

"Renton has been awesome to work with." Norwood stated. "We needed titanium springs for the front Penske's as well as the odd-ball Fox shocks that we're using on the rear suspension. We supplied patterns and they wound the springs from titanium alloy to the exact specifications we needed."

The rear suspension is a unique system devised to allow enough room under the rear of the car for a massive carbon-fiber tunnel that was CAD designed by aerodynamics expert Dejan Matic to greatly enhance high speed stability without killing the top-end speed.

Motorcycle-style "swing arms" are mounted to the rear of the driver's compartment and a pair of lightweight Fox shock absorbers sourced from Fox's Mountain Bike catalog keep the rear-end under control. Not only is this system very rigid, it's also remarkably light. Once again, the center of gravity is kept as low as possible. The swing arms were fabricated in-house and NORAD's ace machinist, Tommy Todd, manufactured the spindles from heat-treated billet steel bar.

The steering rack was also selected with weight in mind. Supplied by Flaming River Products, the lightweight Mustang-based rack is mounted to the rear of the front-axle assembly with a set of custom-machined billet aluminum brackets. The rack was also put on a diet by the NORAD crew to shave a few ounces from the overall weight. To finish the steering assembly, a pair of Jerry Bickel universal joints were mounted on a custom shaft.

Finally, the floors in the NORAD Celica are entirely manufactured from carbon fiber except where the rules dictate that steel must be used. As with every other aspect of this ground-breaking machine, the quality is top-notch and the execution is impeccable.

Norwood's philosophy throughout this project has been to leave as little on the table as possible. In a sport where thousandths of a second can make the difference between winning and losing, Norwood is prepared to go to extreme lengths to save a few ounces or add a few mph.

"At the end of the day, I'm trying to push the limits in front-wheel-drive drag racing." Norwood said.

"The 2004 season will be very competitive and there are a lot of new cars coming out with a lot of new ideas incorporated into them. My job is to try and make sure that Christian Rado is leading the pack when the season comes to an end. If I compromise, I'm just shooting myself and the whole team in the foot. We're determined to win and if we have to push the limits to do that, then so be it."