| NORAD Toyota Celica - Project NORAD Part 2

| NORAD Toyota Celica - Project NORAD Part 2 The best Pro FWD racecars generate around 1100 hp from their four-cylinder powerplants. In this second installation of Project NORAD, Turbo looks at the development of Christian Rado's new Toyota 3RZ engine in its early stages.

Toyota's 3RZ was designed as a engine for the Tacoma mid-sized pickup, so it generates lots of torque at low rpm. In stock form, the 3RZ develops 150 hp at 4800 rpm and 177 lb-ft of torque at 4000 rpm. That's not what a race-winning performance is made of-or is it?

"The Toyota 3RZ makes a lot of sense for a lot of reasons," says Bob Norwood. It's a cast-iron block so it's strong, though it's much heavier than it would be if it was made of aluminum. Also, its square design allows for equal bore and stroke, which with the right components, can really rev this engine without breaking it. Lastly, the large displacement of the 3RZ (at almost 2.7 liters, it's a very large four-cylinder) means it can make more power.

"I want to make at least 1400 hp," explains Norwood. "We'll need to twist this motor up to 11,000 rpm and get boost levels of 50 to 60 psi to achieve our performance goals." With this in mind, Norwood is redesigning the pickup engine with the energy of a four-year-old in need of a dose of Ritalin.

Chris Rado and his WORLD Racing team already laid the groundwork for the 3RZ over the last two years, identifying the weaknesses of the stock 3RZ. This helps Norwood avoid some of the problems encountered with the current version.

One major issue involves valve shims. Ken Goslin, Chris' crew chief, says, "They simply won't stay in place if the engine is revved past our current 10,000-rpm redline. It looks like it's caused by the buckets flexing and distorting, so we developed thicker buckets and these, along with heavier valve springs, have helped the problem immensely." But the team needed a solution that would eliminate the issue with the new engine.

Overall, the LC Engineering-built engine has been extremely durable. There have been no sealing problems despite the occasional over-boost to 50-plus psi and a lack of O-rings. The bottom end is very strong-typical Toyota over-engineering. In this respect, it's very similar to the Supra 2JZ-GTE engine; you can lean on it pretty hard without breaking it.

"Leaning on it pretty hard" translates to around 980 front-wheel hp on World Racing's Dynojet dyno at around 9800 rpm. That was enough to power this year's car to a stout 8.17 at 179 mph at the NOPI world finals on a less-than-perfect track.

"I'd really like to see a seven from this year's car," says Rado. "I know that with good track conditions and a decent tune-up, the car is more than capable, and it would give us all more incentive to keep pushing the limits with the development of the 2004 NORAD Celica."

Norwood is already developing answers to the current issues and, with half an eye on the future, is designing the NORAD 3RZ to be bulletproof.

"This engine has the potential to dominate in 2004. My job is to make that happen," he says.

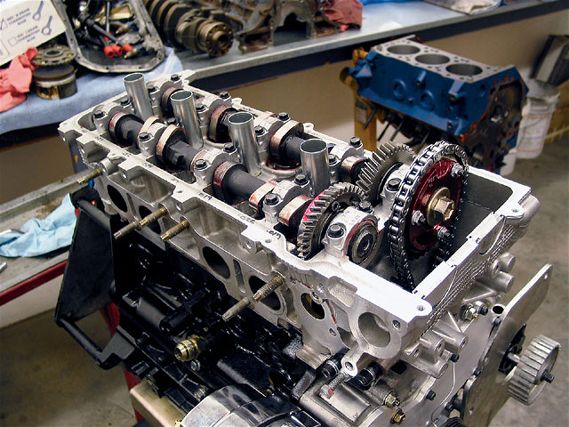

Head Games

The heart of any engine is the cylinder head. Norwood took a hard look at the head and decided that, as good as it was, there was much more potential in the head if he reworked it. The stock ports were squeezed together and were low in the casting, which is fine in a truck engine, but not good for an ass-kicking race engine.

"What I wanted was a direct shot at the back face of the valves and I wanted to be able to position an individual injector behind each valve," says Norwood. "This engine is all about high-rpm flow, so we don't need to concern ourselves with slow-speed swirl and other tricks that enhance low-rpm driveability. Our ports need to be as straight as possible, and to do that, we had to relocate them."

So Norwood consulted with cylinder head guru, Trevor Johnson. Johnson, whose facility is only a couple of miles from Norwood's Rockwall, Texas, shop, is a trade secret in the world of performance tuning. Many of the companies you see advertising performance heads actually use Johnson to do the R&D and more often than not, the actual porting of their heads.

"First we had to weld the stock ports up entirely," explains Johnson. "To allow us to do that without distorting the cam journals and other machined surfaces, Tommy Todd manufactured tooling to keep everything aligned. He machined a 4-inch thick torque plate that bolts to the head where the block would normally be and he also made some rods that bolt into the cam journals in place of the cams. Finally, he manufactured aluminum plugs that install into the cam bucket bores to prevent them from distorting."

Then the head was heated in an oven to 400 degrees and Johnson cranked up his TIG welder. More than 100 hours later, the stock ports were completely welded and the water passages in the head had been eliminated as a safeguard against head gasket failure under extreme boost. The long and tedious process of layering weld upon weld was complete and Johnson was ready to machine the first stage of the relocated ports.

"I moved the outer ports out so they're directly in line with the valves on the intake and exhaust sides. The ports were also lifted by more than 1 inch to give us a straight shot at the reverse side of the valve," says Johnson. The intake ports are shaped like flattened ovals. This shape gave them room to place the injectors side by side and directly in line with each valve while still maintaining airflow velocity and port volume.

On the exhaust side, the whole plan is to evacuate the spent gases as quickly as possible. Once again the ports are centralized behind the valves and are lifted to give a cleaner path to the exhaust manifold and turbocharger.

With the ports machined to rough specs, Johnson's next step involved many hours of grinding and polishing by hand. Trevor dedicated many hours on his Superflow flow-bench to making changes to the size and shape of the ports using epoxy as a medium. Every change is tested and the results recorded at various valve lifts. At the end of the day when the port is optimized, Trevor makes the final grinds and the head is ready for final assembly.

After double-checking all the mating surfaces and camshaft journals, state-of-the-art parts from Ferrea were installed in the head. The titanium intake valves are 1mm oversize; the stock-sized exhaust valves are manufactured from Inconel. Springs were custom wound with an opening pressure of 130 pounds and titanium retainers and locks lower the weight for high-rpm reliability.

The finishing touch is an answer to the shim problems that have haunted the team with the 2003 engine. Rather than try to keep shims in place, either above or below the bucket, Norwood eliminated the shims altogether. The 2004 NORAD 3RZ features cam-follower buckets that are precisely machined so shims aren't required.

A large selection of custom buckets had to be manufactured to allow for adjustment, but Norwood feels the expense and trouble are worthwhile. "The valvetrain has to be 100 percent reliable if we're going to twist this engine to 11,000 rpm and beyond. This is a simple answer to the problem and it works."

Since the NORAD engine is belt driven, not chain driven, Johnson removed the front 4 inches of the head casting and machinist Tommy Todd produced a custom billet-aluminum cam cover. This cam cover and various other trick parts will be replicated in carbon fiber and become a NORAD product for the 2004 season.

All the work done to the cylinder head will be worth it if performance is up to expectations. Now the task of modifying the "production" heads falls to the capable crew at LC Engineering in Lake Havasu, Ariz.

Testing on the flowbench wasn't completed at the time of writing, but we'll have comparison numbers between the stock, race-ported stock and NORAD heads in our next article, along with the story of Team NORAD's search for a bulletproof block and rotating assembly.