There’s nothing simpler than a wheel, right? Evidence of the first wheeled vehicles goes back to Europe and Southwest Asia, 3500 BC. This may not seem fathomable by today’s standards, but the ease of transporting goods with horse and ox-pulled carts was cutting-edge technology at the time. And hard one-piece wheels of clay and wood met the demand.

Thousands of years into the future, the need to increase the durability of wheels came into play. Iron and steel bands were used to cover the weaker contact surface of wooden wheels. Some believe the origin of the word tire is based on the term “attire,” related to “dressing” the wheel.

We’re all familiar with the name Dunlop when talking modern tire manufacturers. However, John Dunlop was the man who initiated the pneumatic (air filled) tires we travel on in the 21st century. It’s an interesting story!

In 1888, John Boyd Dunlop, owner of an Ireland-based veterinary practice, had a son with a medical condition that caused headaches during the jarring ride on his tricycle. Dunlop, with assistance from the child’s doctor, used an inflated tube of sheet rubber on the tricycle’s metal wheels to cushion the ride. This inflated tire/rim combination also demonstrated lower resistance rolling across rough surfaces. And thus the tire as we know it was born.

Big Moments In The History Of Tire Devolvement

1844 – Charles Goodyear, years before tires hit the streets, introduced vulcanization, a process making rubber waterproof, elastic, and more resilient to temperature.

1904 -- Frank Seiberling, founder of Goodyear Tire & Rubber, developed the mountable rim (tires were previously glued to the rim), allowing owners to repair their own flats.

1908 – Seiberling also invented grooved tires (tread) to aid in traction.

1910 – B.F. Goodrich Company added carbon to rubber for increased tire longevity.

1911 – Philip Strauss produced the first successful automotive tires, marketed by Hardman Tyre & Rubber Company.

1937 – B.F. Goodrich began the use of synthetic rubber tires (Chemigum).

1946 – Michelin developed the first marketable radial-ply tires (the “X” tire).

| 006 Tires Can Talk Cutaway Plies And Belts Radial Construction

Bias Ply

Automotive tires originated with a bias ply constructed body (carcass) beneath the outer tread. Using plies or cords of polyester, steel, and other materials, intertwined with rubber, strengthened the tire and provided the needed stability for road contact under heavy loads. Bias ply tire construction begins with the cords crisscrossed at 60-degree angles from the direction of rotation. The angles then vary up the sidewalls to the wire-enforced beads (lips) at final construction.

Radial (today’s standard)

Radial tires are very similar to bias ply but maintain the cords at 90-degree angles, going straight across from bead to bead. This eliminates the friction caused by the crisscrossed cords contacting each other. The reduction in rolling friction increases fuel economy. Steel belts were also added between the ply body and tread to increase strength and provide puncture resistance (i.e. steel-belted radial).

Visually comparing radial with bias ply tires, you’ll notice more of a bow at the sidewall where a radial design contacts the road, as if the tire was low on air. This added flexibility at the sidewall of a radial prevents the tread stature from altering during various driving conditions, therefore maintaining a stronger footprint with the road and increasing traction.

Most Common Tire Types

OK, tires are all round, although we’ve seen several that were almost square following hard miles. Aside from that, there are all kinds of designs and sizes specific to vehicles, terrain, and driving conditions. The vast range includes the temporary spare in your car’s trunk, a Goodyear slick twisted by a 10,000hp Top Fuel dragster, and a big-ass mudder for off-road extremes.

All-Season – Most common OEM tires, usable in dry, wet, and snowy conditions. They have deep water channels to prevent hydroplaning but use a hard rubber compound to increase tire life.

Touring – Smooth, quiet, and with enhanced handling characteristics for ideal weather conditions. A step down from all-season tires on cold/wet roadways.

High-Performance – Driving a sports car? This is the way to go. If not, the compromises outweigh the advantages. High performance tires are designed for high-speed handling, using a softer rubber compound to help stick to hot/dry pavement, at the expense of tread life and snow traction.

Winter – If a geographic location warrants the need for optimal traction in rain, snow, and icy conditions, winter tires are a must. Some folks keep two sets of wheels for a quick swap from all-season to winter tires during the cold months.

Light Truck – These are often broken down by light truck and SUV. More of an off-road tread design for trucks, while leaning toward on-road comfort for SUVs. In either case, there are advantages to the tires being tuned for heavier loads.

Off-Road – Just like it states, they’re not ideal on-road. They have stronger sidewalls to reduce punctures and wider spacing in the tread pattern to reduce clogging from mud, and they often produce increased road noise.

Commercial – Close to off-road but not quite. Used primarily on light work trucks spending a large portion of time in dirt and mud.

| 003 Tires Can Talk Tire Construction

Tire Specifications and Sidewall Information

Example:

[P225] /

[60] [R] [16] [97] [T]

[P225] – The first letter P stands for P-metric, a U.S. standard for passenger car tires. Other designations include LT (light truck), T (temporary spare), and ST (special trailer), while no letter indicates Euro-metric sizes. These designations represent different load capacities and maximum PSI.

The three-digit number refers to tire/tread width in millimeters (225 mm).

[60] -- Aspect ratio, which is the percentage of the tread width that equals the tire/sidewall height.

Multiplying the tread width (225 mm) by the aspect ratio (60 percent or 0.6) gives the sidewall height (135 mm).

[R] – Radial design carcass (plies at 90 degrees, bead-to-bead).

[16] – Wheel diameter in inches.

[97] – Load index: Rating of maximum weight tire can handle at maximum PSI (in this case, 1,609 pounds). Tire load index charts are available to help decipher this code.

[T] – Speed rating (maximum sustained speed capability).

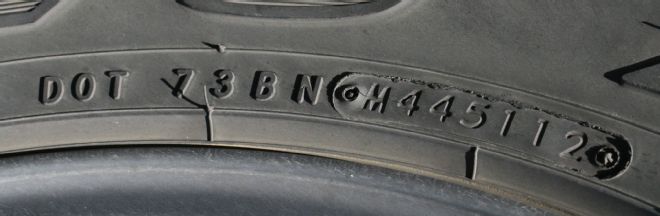

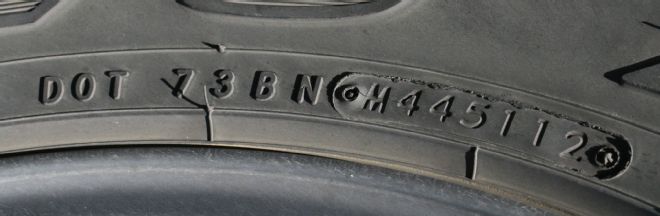

| 008 Tires Can Talk Dot Numbers Date And Place Of Manufacture

Department of Transportation Safety Code (DOT)

Example:

DOT [B9YR] [UJNX] [5008]

[B9YR] [UJNX] – This is the tire’s identification number. First two characters indicate the manufacturer and plant.

[5008] – Date manufactured: First two digits are the week and last two digits indicate year. In this case, the tire was manufactured on the 50th week of 2008, or sometime between December 8 and December 14.

UTQG Code: Uniform Tire Quality Grading by the NHTSA

Example:

TREADWEAR [300] TRACTION [A] TEMPERATURE [B]

TREADWEAR [300] – Ratings of 100 and up, higher numbers indicate the tire wore better on a government test track. A tire with a rating of 300 should last 3 times longer than the base 100-rated tire. These ratings only apply within the specific manufacturer’s line of tires and cannot be compared directly across manufacturers.

TRACTION [A] – AA, A, B, or C. Measurement of straight ahead wet braking under controlled conditions. AA is the best, C is acceptable.

TEMPERATURE [B] – A, B or C. A grade of a tire’s resistance to generating heat in a laboratory environment. Sustained high temperatures degenerate a tire and reduce longevity. A is the best, C is the minimum required.

| TTRP 160300 SHOP 02 LR

Proper Tire Maintenance

Tire Pressure: It doesn’t get much more important than PSI, and more vehicles coming equipped with tire pressure monitoring systems makes it easier to keep track. Always best to inflate to the manufacturer’s specifications. Low inflation will cause excessive tire where on the outer edges, overinflated at the center of the tread. Either can be dangerous during adverse driving conditions.

Rotate: Typically every 5,000 to 7,000 miles, front to rear, crossing two of them in the process. Eliminate crossing with directional tires or left/right rims. Eliminate front-to-rear rotation if the wheels are designated/sized front and rear.

There’s an odd contradiction to tire rotation. Front tires wear faster than the rear due to steering and common front-wheel drivetrains. So we rotate the more worn tires from the front to the rear. The safety drawback is hydroplaning. Tires with less tread depth are more apt to hydroplane on a wet road, and a vehicle is more likely to lose control when the rear tires hydroplane, as opposed to the front. So, for safety, we want the better tires in the rear. The compromise is to rotate on a regular basis so the difference in front and rear tire tread depth is keep to a minimum. And when replacing two tires, mount the new tires on the rear. If the other two are significantly worn, the best bet is replacing all four.

Wheel Alignment: Want the most miles from your new tires? Have a wheel alignment performed in conjunction. Camber angle out of specs will cause excessive wear at the inner or outer edges of the tread. Toe angle out of range will induce a feathered type wear pattern, and eventually high and low spots across the tread (cupping).

New Tires: Stick with the OEM size, load, and speed ratings. It’s not recommended but many folks (shops) will install two new tires that are different models than the two remaining. But never mismatch with two different model tires side-to-side.

A rule of thumb is quality is reflected by the price of the tire. Always best to go with big-name tire manufacturers. If you haven’t heard of the make, there’s a reason.

Some newer tire pressure monitoring systems no longer use pressure sensors in the wheels. They incorporate the electronic stability control system to determine low pressure by wheel speed. Using incorrect (mismatched) tire size, load, or speed ratings can cause the system to misinterpret and activate the low tire-pressure warning indicator, even when the pressure is correct.

When is it time to replace tires that have worn uniformly? Most have wear indicators; small lines of rubber inside the tread grooves which are two millimeters in depth from a bald tire. The majority of state safety inspections consider 2 mm of remaining tread the failure point. It’s safest to replace tires before they go that far. The more shallow the tread, the more likely to hydroplane.

Older tires with good tread should also be replaced. The time-line varies from 6 to 10 year of age, depending on whom you ask. However, visible dry-rot cracks in the rubber should be a red flag.

| 006 Tires Can Talk Cutaway Plies And Belts Radial Construction

Bias Ply

Automotive tires originated with a bias ply constructed body (carcass) beneath the outer tread. Using plies or cords of polyester, steel, and other materials, intertwined with rubber, strengthened the tire and provided the needed stability for road contact under heavy loads. Bias ply tire construction begins with the cords crisscrossed at 60-degree angles from the direction of rotation. The angles then vary up the sidewalls to the wire-enforced beads (lips) at final construction.

Radial (today’s standard)

Radial tires are very similar to bias ply but maintain the cords at 90-degree angles, going straight across from bead to bead. This eliminates the friction caused by the crisscrossed cords contacting each other. The reduction in rolling friction increases fuel economy. Steel belts were also added between the ply body and tread to increase strength and provide puncture resistance (i.e. steel-belted radial).

Visually comparing radial with bias ply tires, you’ll notice more of a bow at the sidewall where a radial design contacts the road, as if the tire was low on air. This added flexibility at the sidewall of a radial prevents the tread stature from altering during various driving conditions, therefore maintaining a stronger footprint with the road and increasing traction.

Most Common Tire Types

OK, tires are all round, although we’ve seen several that were almost square following hard miles. Aside from that, there are all kinds of designs and sizes specific to vehicles, terrain, and driving conditions. The vast range includes the temporary spare in your car’s trunk, a Goodyear slick twisted by a 10,000hp Top Fuel dragster, and a big-ass mudder for off-road extremes.

All-Season – Most common OEM tires, usable in dry, wet, and snowy conditions. They have deep water channels to prevent hydroplaning but use a hard rubber compound to increase tire life.

Touring – Smooth, quiet, and with enhanced handling characteristics for ideal weather conditions. A step down from all-season tires on cold/wet roadways.

High-Performance – Driving a sports car? This is the way to go. If not, the compromises outweigh the advantages. High performance tires are designed for high-speed handling, using a softer rubber compound to help stick to hot/dry pavement, at the expense of tread life and snow traction.

Winter – If a geographic location warrants the need for optimal traction in rain, snow, and icy conditions, winter tires are a must. Some folks keep two sets of wheels for a quick swap from all-season to winter tires during the cold months.

Light Truck – These are often broken down by light truck and SUV. More of an off-road tread design for trucks, while leaning toward on-road comfort for SUVs. In either case, there are advantages to the tires being tuned for heavier loads.

Off-Road – Just like it states, they’re not ideal on-road. They have stronger sidewalls to reduce punctures and wider spacing in the tread pattern to reduce clogging from mud, and they often produce increased road noise.

Commercial – Close to off-road but not quite. Used primarily on light work trucks spending a large portion of time in dirt and mud.

| 006 Tires Can Talk Cutaway Plies And Belts Radial Construction

Bias Ply

Automotive tires originated with a bias ply constructed body (carcass) beneath the outer tread. Using plies or cords of polyester, steel, and other materials, intertwined with rubber, strengthened the tire and provided the needed stability for road contact under heavy loads. Bias ply tire construction begins with the cords crisscrossed at 60-degree angles from the direction of rotation. The angles then vary up the sidewalls to the wire-enforced beads (lips) at final construction.

Radial (today’s standard)

Radial tires are very similar to bias ply but maintain the cords at 90-degree angles, going straight across from bead to bead. This eliminates the friction caused by the crisscrossed cords contacting each other. The reduction in rolling friction increases fuel economy. Steel belts were also added between the ply body and tread to increase strength and provide puncture resistance (i.e. steel-belted radial).

Visually comparing radial with bias ply tires, you’ll notice more of a bow at the sidewall where a radial design contacts the road, as if the tire was low on air. This added flexibility at the sidewall of a radial prevents the tread stature from altering during various driving conditions, therefore maintaining a stronger footprint with the road and increasing traction.

Most Common Tire Types

OK, tires are all round, although we’ve seen several that were almost square following hard miles. Aside from that, there are all kinds of designs and sizes specific to vehicles, terrain, and driving conditions. The vast range includes the temporary spare in your car’s trunk, a Goodyear slick twisted by a 10,000hp Top Fuel dragster, and a big-ass mudder for off-road extremes.

All-Season – Most common OEM tires, usable in dry, wet, and snowy conditions. They have deep water channels to prevent hydroplaning but use a hard rubber compound to increase tire life.

Touring – Smooth, quiet, and with enhanced handling characteristics for ideal weather conditions. A step down from all-season tires on cold/wet roadways.

High-Performance – Driving a sports car? This is the way to go. If not, the compromises outweigh the advantages. High performance tires are designed for high-speed handling, using a softer rubber compound to help stick to hot/dry pavement, at the expense of tread life and snow traction.

Winter – If a geographic location warrants the need for optimal traction in rain, snow, and icy conditions, winter tires are a must. Some folks keep two sets of wheels for a quick swap from all-season to winter tires during the cold months.

Light Truck – These are often broken down by light truck and SUV. More of an off-road tread design for trucks, while leaning toward on-road comfort for SUVs. In either case, there are advantages to the tires being tuned for heavier loads.

Off-Road – Just like it states, they’re not ideal on-road. They have stronger sidewalls to reduce punctures and wider spacing in the tread pattern to reduce clogging from mud, and they often produce increased road noise.

Commercial – Close to off-road but not quite. Used primarily on light work trucks spending a large portion of time in dirt and mud.

| 003 Tires Can Talk Tire Construction

Tire Specifications and Sidewall Information

Example: [P225] / [60] [R] [16] [97] [T]

[P225] – The first letter P stands for P-metric, a U.S. standard for passenger car tires. Other designations include LT (light truck), T (temporary spare), and ST (special trailer), while no letter indicates Euro-metric sizes. These designations represent different load capacities and maximum PSI.

The three-digit number refers to tire/tread width in millimeters (225 mm).

[60] -- Aspect ratio, which is the percentage of the tread width that equals the tire/sidewall height.

Multiplying the tread width (225 mm) by the aspect ratio (60 percent or 0.6) gives the sidewall height (135 mm).

[R] – Radial design carcass (plies at 90 degrees, bead-to-bead).

[16] – Wheel diameter in inches.

[97] – Load index: Rating of maximum weight tire can handle at maximum PSI (in this case, 1,609 pounds). Tire load index charts are available to help decipher this code.

[T] – Speed rating (maximum sustained speed capability).

| 003 Tires Can Talk Tire Construction

Tire Specifications and Sidewall Information

Example: [P225] / [60] [R] [16] [97] [T]

[P225] – The first letter P stands for P-metric, a U.S. standard for passenger car tires. Other designations include LT (light truck), T (temporary spare), and ST (special trailer), while no letter indicates Euro-metric sizes. These designations represent different load capacities and maximum PSI.

The three-digit number refers to tire/tread width in millimeters (225 mm).

[60] -- Aspect ratio, which is the percentage of the tread width that equals the tire/sidewall height.

Multiplying the tread width (225 mm) by the aspect ratio (60 percent or 0.6) gives the sidewall height (135 mm).

[R] – Radial design carcass (plies at 90 degrees, bead-to-bead).

[16] – Wheel diameter in inches.

[97] – Load index: Rating of maximum weight tire can handle at maximum PSI (in this case, 1,609 pounds). Tire load index charts are available to help decipher this code.

[T] – Speed rating (maximum sustained speed capability).

| 008 Tires Can Talk Dot Numbers Date And Place Of Manufacture

Department of Transportation Safety Code (DOT)

Example: DOT [B9YR] [UJNX] [5008]

[B9YR] [UJNX] – This is the tire’s identification number. First two characters indicate the manufacturer and plant.

[5008] – Date manufactured: First two digits are the week and last two digits indicate year. In this case, the tire was manufactured on the 50th week of 2008, or sometime between December 8 and December 14.

UTQG Code: Uniform Tire Quality Grading by the NHTSA

Example: TREADWEAR [300] TRACTION [A] TEMPERATURE [B]

TREADWEAR [300] – Ratings of 100 and up, higher numbers indicate the tire wore better on a government test track. A tire with a rating of 300 should last 3 times longer than the base 100-rated tire. These ratings only apply within the specific manufacturer’s line of tires and cannot be compared directly across manufacturers.

TRACTION [A] – AA, A, B, or C. Measurement of straight ahead wet braking under controlled conditions. AA is the best, C is acceptable.

TEMPERATURE [B] – A, B or C. A grade of a tire’s resistance to generating heat in a laboratory environment. Sustained high temperatures degenerate a tire and reduce longevity. A is the best, C is the minimum required.

| 008 Tires Can Talk Dot Numbers Date And Place Of Manufacture

Department of Transportation Safety Code (DOT)

Example: DOT [B9YR] [UJNX] [5008]

[B9YR] [UJNX] – This is the tire’s identification number. First two characters indicate the manufacturer and plant.

[5008] – Date manufactured: First two digits are the week and last two digits indicate year. In this case, the tire was manufactured on the 50th week of 2008, or sometime between December 8 and December 14.

UTQG Code: Uniform Tire Quality Grading by the NHTSA

Example: TREADWEAR [300] TRACTION [A] TEMPERATURE [B]

TREADWEAR [300] – Ratings of 100 and up, higher numbers indicate the tire wore better on a government test track. A tire with a rating of 300 should last 3 times longer than the base 100-rated tire. These ratings only apply within the specific manufacturer’s line of tires and cannot be compared directly across manufacturers.

TRACTION [A] – AA, A, B, or C. Measurement of straight ahead wet braking under controlled conditions. AA is the best, C is acceptable.

TEMPERATURE [B] – A, B or C. A grade of a tire’s resistance to generating heat in a laboratory environment. Sustained high temperatures degenerate a tire and reduce longevity. A is the best, C is the minimum required.

| TTRP 160300 SHOP 02 LR

Proper Tire Maintenance

Tire Pressure: It doesn’t get much more important than PSI, and more vehicles coming equipped with tire pressure monitoring systems makes it easier to keep track. Always best to inflate to the manufacturer’s specifications. Low inflation will cause excessive tire where on the outer edges, overinflated at the center of the tread. Either can be dangerous during adverse driving conditions.

Rotate: Typically every 5,000 to 7,000 miles, front to rear, crossing two of them in the process. Eliminate crossing with directional tires or left/right rims. Eliminate front-to-rear rotation if the wheels are designated/sized front and rear.

There’s an odd contradiction to tire rotation. Front tires wear faster than the rear due to steering and common front-wheel drivetrains. So we rotate the more worn tires from the front to the rear. The safety drawback is hydroplaning. Tires with less tread depth are more apt to hydroplane on a wet road, and a vehicle is more likely to lose control when the rear tires hydroplane, as opposed to the front. So, for safety, we want the better tires in the rear. The compromise is to rotate on a regular basis so the difference in front and rear tire tread depth is keep to a minimum. And when replacing two tires, mount the new tires on the rear. If the other two are significantly worn, the best bet is replacing all four.

Wheel Alignment: Want the most miles from your new tires? Have a wheel alignment performed in conjunction. Camber angle out of specs will cause excessive wear at the inner or outer edges of the tread. Toe angle out of range will induce a feathered type wear pattern, and eventually high and low spots across the tread (cupping).

New Tires: Stick with the OEM size, load, and speed ratings. It’s not recommended but many folks (shops) will install two new tires that are different models than the two remaining. But never mismatch with two different model tires side-to-side.

A rule of thumb is quality is reflected by the price of the tire. Always best to go with big-name tire manufacturers. If you haven’t heard of the make, there’s a reason.

Some newer tire pressure monitoring systems no longer use pressure sensors in the wheels. They incorporate the electronic stability control system to determine low pressure by wheel speed. Using incorrect (mismatched) tire size, load, or speed ratings can cause the system to misinterpret and activate the low tire-pressure warning indicator, even when the pressure is correct.

When is it time to replace tires that have worn uniformly? Most have wear indicators; small lines of rubber inside the tread grooves which are two millimeters in depth from a bald tire. The majority of state safety inspections consider 2 mm of remaining tread the failure point. It’s safest to replace tires before they go that far. The more shallow the tread, the more likely to hydroplane.

Older tires with good tread should also be replaced. The time-line varies from 6 to 10 year of age, depending on whom you ask. However, visible dry-rot cracks in the rubber should be a red flag.

| TTRP 160300 SHOP 02 LR

Proper Tire Maintenance

Tire Pressure: It doesn’t get much more important than PSI, and more vehicles coming equipped with tire pressure monitoring systems makes it easier to keep track. Always best to inflate to the manufacturer’s specifications. Low inflation will cause excessive tire where on the outer edges, overinflated at the center of the tread. Either can be dangerous during adverse driving conditions.

Rotate: Typically every 5,000 to 7,000 miles, front to rear, crossing two of them in the process. Eliminate crossing with directional tires or left/right rims. Eliminate front-to-rear rotation if the wheels are designated/sized front and rear.

There’s an odd contradiction to tire rotation. Front tires wear faster than the rear due to steering and common front-wheel drivetrains. So we rotate the more worn tires from the front to the rear. The safety drawback is hydroplaning. Tires with less tread depth are more apt to hydroplane on a wet road, and a vehicle is more likely to lose control when the rear tires hydroplane, as opposed to the front. So, for safety, we want the better tires in the rear. The compromise is to rotate on a regular basis so the difference in front and rear tire tread depth is keep to a minimum. And when replacing two tires, mount the new tires on the rear. If the other two are significantly worn, the best bet is replacing all four.

Wheel Alignment: Want the most miles from your new tires? Have a wheel alignment performed in conjunction. Camber angle out of specs will cause excessive wear at the inner or outer edges of the tread. Toe angle out of range will induce a feathered type wear pattern, and eventually high and low spots across the tread (cupping).

New Tires: Stick with the OEM size, load, and speed ratings. It’s not recommended but many folks (shops) will install two new tires that are different models than the two remaining. But never mismatch with two different model tires side-to-side.

A rule of thumb is quality is reflected by the price of the tire. Always best to go with big-name tire manufacturers. If you haven’t heard of the make, there’s a reason.

Some newer tire pressure monitoring systems no longer use pressure sensors in the wheels. They incorporate the electronic stability control system to determine low pressure by wheel speed. Using incorrect (mismatched) tire size, load, or speed ratings can cause the system to misinterpret and activate the low tire-pressure warning indicator, even when the pressure is correct.

When is it time to replace tires that have worn uniformly? Most have wear indicators; small lines of rubber inside the tread grooves which are two millimeters in depth from a bald tire. The majority of state safety inspections consider 2 mm of remaining tread the failure point. It’s safest to replace tires before they go that far. The more shallow the tread, the more likely to hydroplane.

Older tires with good tread should also be replaced. The time-line varies from 6 to 10 year of age, depending on whom you ask. However, visible dry-rot cracks in the rubber should be a red flag.