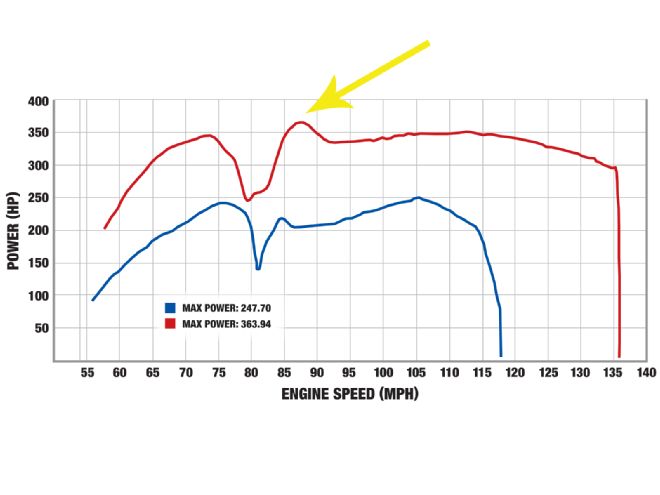

We talk about dynamometer numbers all the timeso often, in fact, that they are treated as absolute truth. But should they be? Or are all these numbers we speak of meaningless? As it turns out, dyno numbers are very reliable ways of measuring horsepower, but they are only as good as the information and the operator that goes into the dyno run. Can you give fake dyno numbers? You sure can: just make up a sheet on your computer in Photoshop. But for those who are honest about it or who use dynos as a tuning tool, they are very useful.

| dyno Truths classic Dodge Pickup On Dyno

The simplest definition of a dynamometer is that it is a machine that’s capable of measuring force, and once that is measured, horsepower and torque can then be calculated. In the diesel performance industry, driving the vehicle onto, and having the vehicle accelerate a large roller is the most common way to measure force, and this type of dynamometer is called a chassis dyno.

Dyno Differences

Inertia Dynos

The easiest dyno to explain is called an inertia chassis dyno. You’ve seen these all over the pages of Diesel Power, and they are usually defined by a big, single roller, and the word “Dynojet.” Dynojet dynos were the first affordable inertia dyno in the industry and are still the gold standard. They’re based on the time it takes to accelerate a very heavy steel drum, much the same as a heavy vehicle accelerates down the dragstrip. Since these dynos are simple, they are relatively inexpensive (prices start at about $20,000), meaning many shops can afford them. While they can’t provide a varying load for spool or rpm, or diagnostic testing, they are good at measuring horsepower and torque and will give a very accurate reading.

| When strapping a vehicle down on the dyno, it’s important to use front and back straps—and to get them as tight as possible. Notice that four straps are used in the back, and two of them are crossed to ensure the vehicle doesn’t shift side to side on the dyno.

Load-Cell Dynos

A load-cell dyno is the type that is more popularly used by shops as tuning tools. Load cells use an eddy current brake to create magnetic swirls that place a stopping force on the rollers, creating a load. The load is also variable and can be used to produce a steady-state dyno run, a timed run, or even a backward dyno pull, in which the rpm drops instead of rises. Because of this technology (which is also used to brake roller coasters and subways), a load-cell dyno can be twice as expensive as an inertia dyno, but it can also be used in many different ways. Load-cell dynos can also place more of a load on the vehicle than an inertia dyno, and careful steps must be taken to keep the tires from spinning on the rollers during test runs lasting longer than a few seconds.

Engine Dynos

Although less common than either load or inertia chassis dynos, engine dynos can also be used to measure an engine’s horsepower. Mostly used to test sled pulling engines with very large turbochargers, engine dynos are a great way of measuring raw horsepower without any associated drivetrain loss. There’s also no tire slippage or rpm window to worry about, but you have to pull the engine to run it on an engine dyno, which makes them far less popular.

Can You Trust Your Results?

The short answer is that, in most cases, yes, you can. That doesn’t mean the results can’t be manipulated, or that they may not be indicative of what you would see on the street. A lower level of load can cause diesel trucks to make less boost, the vehicle can spin the tires on the dyno, or the operator can put in an inflated correction factor—any of these will throw the numbers off. In most cases, we’ve seen about a 10 percent variance from dyno to dyno, which is quite a bit—but won’t make a 400hp truck act like a 900hp one. We have seen very odd results from less expensive and small roller dynos, however, so if you’re a shop owner looking to purchase one, we’d stick with the type mentioned in this article.

While bragging rights are fun, the ultimate use of a dyno is to tune and refine the vehicle for its intended use and evaluate changes. There’s a lot of guessing involved in seat-of-the-pants power numbers, but for a hundred bucks or so, you can stop guessing and know for sure. And that’s what dynos are all about.

Dyno Dictionary

Brake Boosting: This is when the driver of the vehicle drags the brakes in order to build boost, before starting the dyno run. This is particularly helpful in large-turbo trucks in order to ensure they are under plenty of load at the start of the dyno run.

| Perhaps the best way to get good numbers on a dyno is to talk with someone who has already made a bunch of runs. Dmitri Millard has made hundreds upon hundreds of dyno runs on a variety of different dynos with his trucks, so he was a great resource when it came to helping others at events. The joke was, “Do whatever Dmitri does, and you’ll be fine.”

Correction Factor: Perhaps the hottest topic in dynoing, a correction factor is a number that corrects from dyno to dyno (say, Superflow to Dynojet) or corrects for temperature and pressure (basically altitude). This correction factor will multiply the existing uncorrected horsepower number by a percentage—up to 20 or 30 percent in some cases. On diesels, correction factors will usually overcorrect the numbers and make them appear higher than they really are, but the jury is still out on how much, if any, correction factor should be applied.

Drum: Also known as a roller, a drum is the round rolling device the vehicle accelerates in order to give a horsepower reading.

Dyno: Also known as a dynamometer, the dyno is a device for measuring force. From that force, torque and horsepower can be calculated.

Eddy Current Brake: On a load dyno, an eddy current, or magnetic brake, is used to generate force or load against the tires of the vehicle. On an engine dyno, water is often used as a holding medium instead of magnetic forces. This is known as a water brake.

Load: The amount of resistance placed against the tires of the vehicle while it is on the dyno. On an inertia dyno, this is constant, but on a load dyno, it is variable. Load can also be changed by dynoing in a different gear in the transmission. While the power numbers will be similar, dynoing in the highest gear possible will usually yield the best results.

Rear-wheel Horsepower (RWHP): Because all chassis dynos operate by running the drive wheels on the rollers, a rear-wheel-drive vehicle’s power is abbreviated with “rwhp,” which is the simplified and shortened version of rear-wheel horsepower. Similarly, all-wheel horsepower would be “awhp,” while front-wheel horsepower would be “fwhp.”

Tach Signal: To get an rpm signal and calculate torque, a small piece of reflective tape is placed on the balancer of the engine. A sensor on the dyno is then aimed at the tape and used to generate an rpm signal. If the engine moves enough during the dyno pull to throw the sensor off, this is called “losing the tach signal,” which can result in inaccurate readings.